The Toolbox

A list of the police surveillance tools at the disposal of the city of New Orleans

One of the biggest hurdles to surveillance oversight is simply accounting for all the tools at the city's disposal.

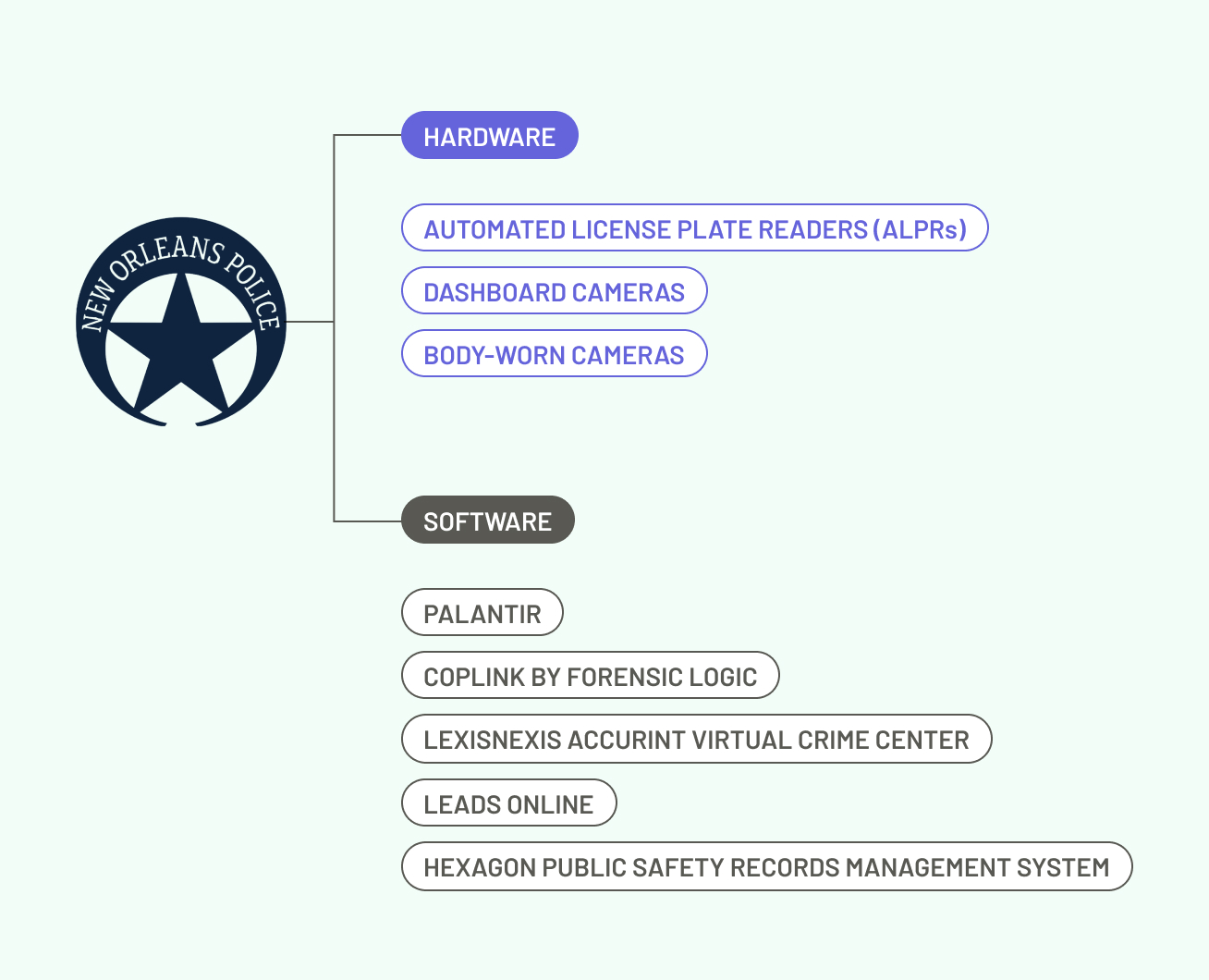

New Orleans’ surveillance apparatus is made up of a constantly-changing collection of hardware, software and databases managed by various city departments, outside law enforcement agencies and private organizations.

Seattle, Oakland and other cities with stricter surveillance regulations now mandate “master lists” of the city’s surveillance tools or annual reports from city departments that use surveillance technology. But New Orleans, like most cities, doesn’t require that type of public disclosure or internal tracking.

The following is a list of surveillance hardware and software employed by or accessible to New Orleans law enforcement from 2017 to 2020 based on city contracts and purchase orders obtained by The Lens through public records requests, as well as product information from press releases and vendor websites.

Due to the expansive number of city technologies that could potentially fit the city’s official definition of “surveillance technology,” this list is restricted to technology primarily related to criminal law enforcement. It does not include, for example, the license plate readers managed by the Department of Public Works to automate parking enforcement.

The Real Time Crime Center

The Real Time Crime Center is the central monitoring hub for 975 live feeds from cameras installed around the city.

Additional law enforcement data flows to the RTCC from the city’s 911 call center. The RTCC also houses advanced software to search and analyze video and data.

The RTCC is not controlled directly by the New Orleans Police Department. It’s managed by the New Orleans Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness. It runs surveillance operations on behalf of the NOPD, but it works with other law enforcement agencies as well, including the FBI, the Louisiana State Police, Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, university police departments, and more.

The RTCC used to be able to access and search the data captured by the city’s fleet of license plate readers (primarily managed by the NOPD), but it lost that ability after a December 2019 cyberattack and hasn’t been able to regain that function as of April 2021, according to an RTCC spokesperson.

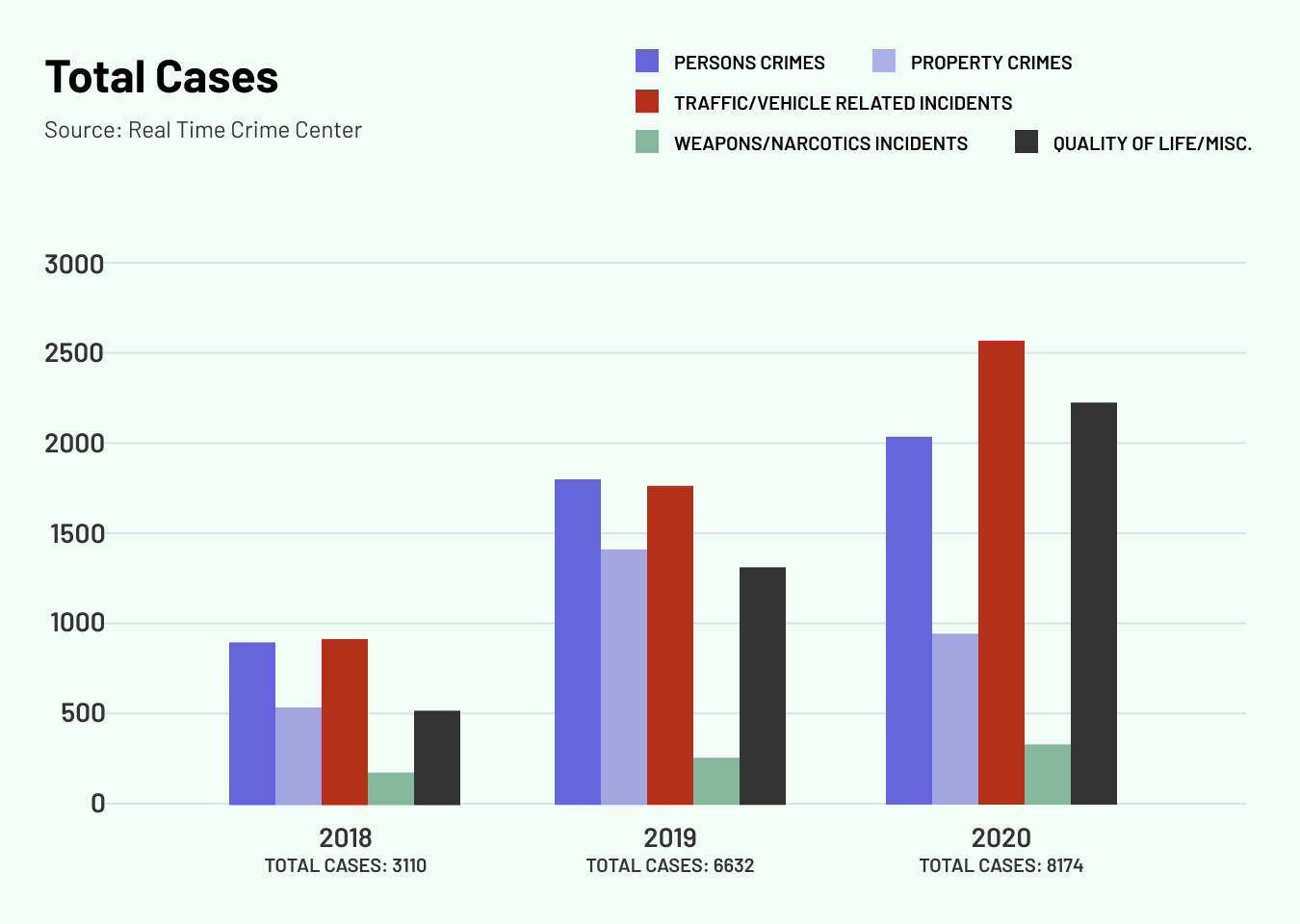

The central policy document for the RTCC is a privacy policy that employees are required to sign. Statistics on the RTCC’s operations from 2018 to 2020 — produced by the city and obtained through a public records request — are available here.

RTCC Hardware

As of February 2021, the Real Time Crime Center monitored live feeds from 555 city-owned cameras and 420 integrated privately owned cameras.

The 555 city-owned cameras are marked with NOPD logos and sometimes have red and blue flashing lights. These cameras are mostly static, but the city can and does move them around intermittently.

Archived Footage

Along with the 975 cameras feeding live footage into the Real-Time Crime Center, the New Orleans Police Department also has access to archived footage from thousands of cameras throughout the city through a camera registry partially controlled by the city, and through the cooperation of a private surveillance camera service called ProjectNOLA. Read more about these two camera programs in the “Partnerships” section below.

Invoices from the city’s primary camera supplier, Active Solutions, show that the city has purchased at least six camera models manufactured by Hikvision and Axis Communications that have varying features, like 360-degree tilt, long-distance zoom and smart tracking that automatically follows moving objects.

Active Solutions also makes its own, in-house cameras with premade encasements, including their “Safe City Cam” and “RDI Cam,” which are used by the city.

The city owns two mobile camera trailers that can be easily moved for specific surveillance targets, according to an RTCC spokesperson. Undated meeting notes from a city public safety meeting illustrate how those trailers can be used, indicating that the city moved the two cameras to intercept a second line parade, leading to “two gun arrests."

The other 420 live camera feeds aren’t owned by the city, but are connected to the RTCC through the Safecam Platinum program. The program allows residents and businesses to give the RTCC access to live feeds from their private surveillance cameras.

The city paid the New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation at least $300,000 from 2018 to 2020 to manage the program. Participating businesses and residents have to pay the camera installation and management costs. The estimated price tag on the Safecam website is $250 per camera, $150 in installation costs and $18 a month for cloud storage.

RTCC policy mandates that both city-owned and Safecam Platinum cameras must be pointing out towards public areas “where no legally protected reasonable expectation of privacy exists.” However, according to Colin Reingold, former litigation director for the Orleans Public Defenders, RTCC cameras posted high on utility poles often catch private spaces like backyards.

“We have seen examples where its clear the real time crime cameras, although they are on public spaces and high up, their capabilities are so strong it can peer into cars, it can peer into windows of structures and capture what's happening from outside from a fairly long distance in what have historically considered private spaces,” Reingold said.

The RTCC footage is stored remotely through the cloud with the company Genetec. Footage is stored for 30 days and then deleted unless flagged by RTCC staff or an NOPD officer, according to RTCC policy.

RTCC Software

Genetec

The Genetec video storage and management software package includes four pieces of software: Security Center, Omnicast, Federation and Stratocast.

Security Center is the central user interface for the software suite.

Omnicast provides video analytics, including motion-sensing alarms on live video and the ability to track individual people, cars and objects in live and archived footage. Genetec’s website says that Omnicast incorporates “3rd party” software and technologies as well.

Genetec’s Federation software allows the RTCC to integrate live footage from privately owned cameras through the city’s Safecam Platinum program. And the Stratocast software allows officers to access RTCC footage remotely on laptops, tablets and smartphones.

Third-Party Software

Several surveillance software products utilized by the city are embedded with, or provide access to, third-party software. The NOPD records management system, for example, is from a company called Hexagon, but provides access to services from Microsoft’s Azure division — an advanced set of analytic tools that includes artificial intelligence. Privacy advocates have expressed concerns that third party software agreements can shroud those relationships from public view. There is also a growing concern about the cybersecurity risk presented by third party software.

Motorola CommandCentral

The Motorola CommandCentral package is a video/data integration and analytics software suite that includes CommandCentral Aware, CommandCentral Analytics and CommandCentral Predictive.

CommandCentral Aware is the central part of the Motorola software package. It integrates video feeds, 911 data, patrol vehicle GPS information and more onto a single interface for RTCC operators. The software also allows operators to “virtually patrol” by watching up to 16 feeds simultaneously.

The city claims that it has never used either CommandCentral Analytics or CommandCentral Predictive, although it does have access to them.

Motorola website description of CommandCentral Analytics: “Put big data to work so you can quickly identify crime trends, track down leads with more accuracy. … Supplement your agency data with 298+ million law enforcement records and 87+ billion public records.”

Motorola website description of CommandCentral Predictive: “Utilize the power of analytics and prediction to identify where, when and what type of crimes will occur with CommandCentral Predictive. Using your Records Management System (RMS) data, the system ‘learns’ from historical data specific to your jurisdiction and creates a prediction model for future crime.”

BriefCam (no longer in use)

BriefCam was included in the original package of software purchased from Motorola. The software “detects, tracks, extracts and identifies people and objects from video, including; men, women, children, clothing, bags, vehicles, animals, size, color, speed, path, direction, dwell time, and more,” according to a press release announcing New Orleans’ purchase of the software.

The software can track individuals based on characteristics from one camera to the next and throughout hundreds of hours of archived footage. The software can also create “heat maps” of dwell time and object interaction based on hours of footage to reveal addresses that have unusually high foot traffic.

The city says it stopped subscribing to BriefCam in 2019.

New Orleans Police Department

The Lens submitted a public records request for all NOPD software contracts, invoices and purchase orders over a nearly three year span. The city responded with a group of documents, but included a message that said, “Please note that the records are all that the Police Department was able to locate after an extensive search; however, it may not represent all responsive records.”

The following list is compiled from those records, as well as responses from an NOPD spokesperson and prior news coverage.

Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs)

ALPRs can be either fixed or mobile. They automatically detect and capture all license plates that come into its view, along with the location, time and date information. The NOPD told The Lens that as of March 2021, the city had 89 total ALPRs — 40 of them are stationary, 10 are portable trailers and 39 are mounted on patrol vehicles.

In August, the city announced that it would be using $1 million in federal coronavirus recovery aid to purchase another 150 to 160 ALPRs.

The ALPR data is managed with the 3M Back Office System Software, which organizes the license plate data and makes it searchable. And it allows officers to create hotlists to automatically alert police when certain license plates pass an ALPR. License plate numbers can be added manually to hotlists whether or not they’ve been implicated in a crime.

Read the NOPD’s license plate reader policy.

In-Car Dashboard Cameras

The federal consent decree with the NOPD mandates in-car cameras for most NOPD vehicles.

The NOPD has 413 dash cameras systems installed on patrol vehicles – 190 from L3 Technologies and 223 from Axon. Each system has two cameras — one front camera filming out the front windshield and one rear camera recording the backseat — for a total of 826 cameras.

The Axon "Fleet 2" cameras, according to the company's website, have infrared capabilities to see at night and with 4x digital zoom. The system can also capture audio from up to 1000 feet away.

The L3 dash camera footage is stored in a server at City Hall. According to the NOPD, the 190 L3 camera systems produced nearly 31 terabytes of video in 2020. The Axon Fleet 2 dash camera footage is stored remotely and accessed through Evidence.com, another Axon product.

Read the NOPD’s in-car camera policy.

Body-Worn Cameras

The NOPD owned and utilized 1,383 Axon body-worn cameras as of March 2021, according to the NOPD. The footage and audio recorded by the cameras are uploaded to Evidence.com.

Read the NOPD’s two body-worn camera policies here and here.

Body Cameras - surveillance or accountability tool?

Police body-worn cameras are often hailed as a great tool for catching police abuses and rebuking phony citizen complaints. The NOPD first mandated body cameras in 2014 as a reform measure.

But they carry big privacy and surveillance implications as well. Body cameras pick up massive amounts of video and audio wherever police go — while walking a beat, working at a protest or parade, looking into someone's car or interviewing a victim or witness in their home.

And the same kind of advanced video analytics applied to RTCC surveillance video are also being used with body camera footage. In 2016, the New Orleans District Attorney’s office obtained software to mine and catalog audio and video captured by body-worn cameras.

“The software creates an audio transcript and record of faces and text in each video through an automated system, which means an officer or investigator can type in a person's name or keywords like drugs and search for when and where it was spoken,” said a 2016 press release.

Privacy advocates worry about additional capabilities being added to body cameras, like license plate readers and facial recognition to identify people in real-time.

The ACLU and the Electronic Frontier Foundation argue that body cameras should be put in place only after cities create policies to ensure the technology is an effective accountability tool and isn’t abused by the police as a surveillance tool.

In New Orleans, advocates have complained about a policy that gives the NOPD superintendent sole discretion over whether body camera footage is released to the public or withheld.

“Overall, we think they can be a win-win—but only if they are deployed within a framework of strong policies to ensure they protect the public without becoming yet another system for routine surveillance of the public,” said an ACLU white paper from 2015.

Palantir Gotham Software (no longer in use)

Gotham is a product made by the major data-mining company Palantir. It’s a data integration, mining and analytics software that includes predictive tools. The NOPD used the software to create a controversial list of the one percent of New Orleans residents with the highest perceived threat of being involved in a gun crime. The NOPD used the software from 2012 until 2018, when The Verge revealed the practice to a largely unknowing public. Then-Mayor Mitch Landrieu chose not to renew the controversial agreement and it expired in 2018.

COPLINK from Forensic Logic (no longer in use)

COPLINK is a data sharing and crime analytics platform that is “designed to help law enforcement organizations solve crimes faster by providing tactical, strategic and command-level access to vast quantities of seemingly unrelated data,” according to its website. The software provides a “Google-like” search of “billions” of documents through “the largest network of law enforcement agencies in America.”

Ronal Serpas, former superintendent of the NOPD, compared COPLINK to the controversial Gotham policing software from Palantir. The two are often described as market rivals.

COPLINK has a number of “modules” that provide analytic and search tools for investigators, including a facial recognition feature. The COPLINK Detect module, according to the website “can quickly narrow down results by finding associations between vague Person, Vehicle, Location, Gang, Firearm, etc. descriptions.” The COPLINK Activity Correlation module uses “unique algorithms [to] monitor incoming information and alert analysts to potentially suspicious activities.” The NOPD didn’t respond to questions about what modules they used or had access to.

The NOPD did not renew its contract with Forensic Logic when it expired in April 2021 and no longer has access to the COPLINK software, an NOPD spokesperson told The Lens.

LexisNexis Accurint Virtual Crime Center

The Accurint Virtual Crime Center is a search tool that gives users access to vast troves of law enforcement data and public records from around the country. It has built in analytic tools including predictive policing.

From the LexisNexis website: “Finding, identifying and verifying identities is a fast easy process with our proprietary technology, LexID. It links cross-jurisdictional agency data with identity information from over 10,000 sources. And it uses our patented linking and clustering method to resolve, match and manage information for more than 276 million U.S. consumer identities.”

According to the website, the data comes from both government sources as well as “commercially available data sources.”

Through LexisNexis, the NOPD has access to a data integration and analytics software called Lumen. Lumen includes facial recognition software, but LexisNexis reportedly disabled that feature in November 2020.

Private sector data

Along with government-collected data, New Orleans also has access to private sector data, like the pawnshop purchase database obtained through LeadsOnline. Other investigatory tools used in New Orleans make vague references to using privately collected data. LexisNexis Accurint Virtual Crime Center, for example, claims to provide access to “commercially available data sources,” on its website.

LeadsOnline

LeadsOnline is an online pawnshop transaction database. According to an invoice to the NOPD, “LeadsOnline software provides unique access to regional pawn shop information, there is also an unparalleled national network of pawn shops reporting into the LeadsOnline System. LeadsOnline has a network of 2600 cities throughout the country and partnerships with industry giants such as Cash America, Pawn America, ecoATM and Best Buy. LeadsOnline has accumulated a database of more than 725 million pawn shop transactions that can be searched by its clients.”

Hexagon Public Safety Records Management System

HxGN OnCall Records: A cloud-based records management system for NOPD documents including arrest records, incident reports and 911 call data.

HcGn OnCall Analytics: A data mining and analytic software that can organize and make sense of the massive troves of NOPD data. The software uses services from Microsoft’s Azure division — an advanced set of tools that includes artificial intelligence and a major supplier of cloud-based surveillance software, according to reporting from The Intercept.

Orleans Parish Communications District

The Orleans Parish Communications District, or OPCD, runs the city’s 911 and 311 systems. It’s a semi-independent, state-created body that was originally created just to handle the 911 system. But in late 2018, the city merged the 911 system with the 311 system — a catch-all non-emergency service request line — and consolidated them under OPCD.

In recent years, OPCD has begun investing in next generation 911, or NG911, technologies that allow 911 centers to collect more data from callers and transmit more data to public safety agencies. The technology seeks to solve traditional issues with legacy 911 systems — like dropped calls, poor location data and situations where a person can’t speak — and adapt to the fact that the majority of 911 calls now come from cell phones rather than landlines.

The technologies also focus on modernizing the way people communicate with 911 operators, like adding text and video chat, and collecting more data from callers’ smartphones, apps and bluetooth connected devices, including precise location data.

According to an OPCD spokesperson, the data collected by these NG911 programs is only collected from 911 calls, not from 311 calls.

Motorola PremierOne

The PremierOne software is the central caller aided dispatch, or CAD, interface for 911 operators. When receiving a call, the system allows operators to quickly compile relevant data — like the caller location, records associated with a certain address, tickets associated with the phone number, building plans, suspect photos and more — and send it to the NOPD and the Real Time Crime Center.

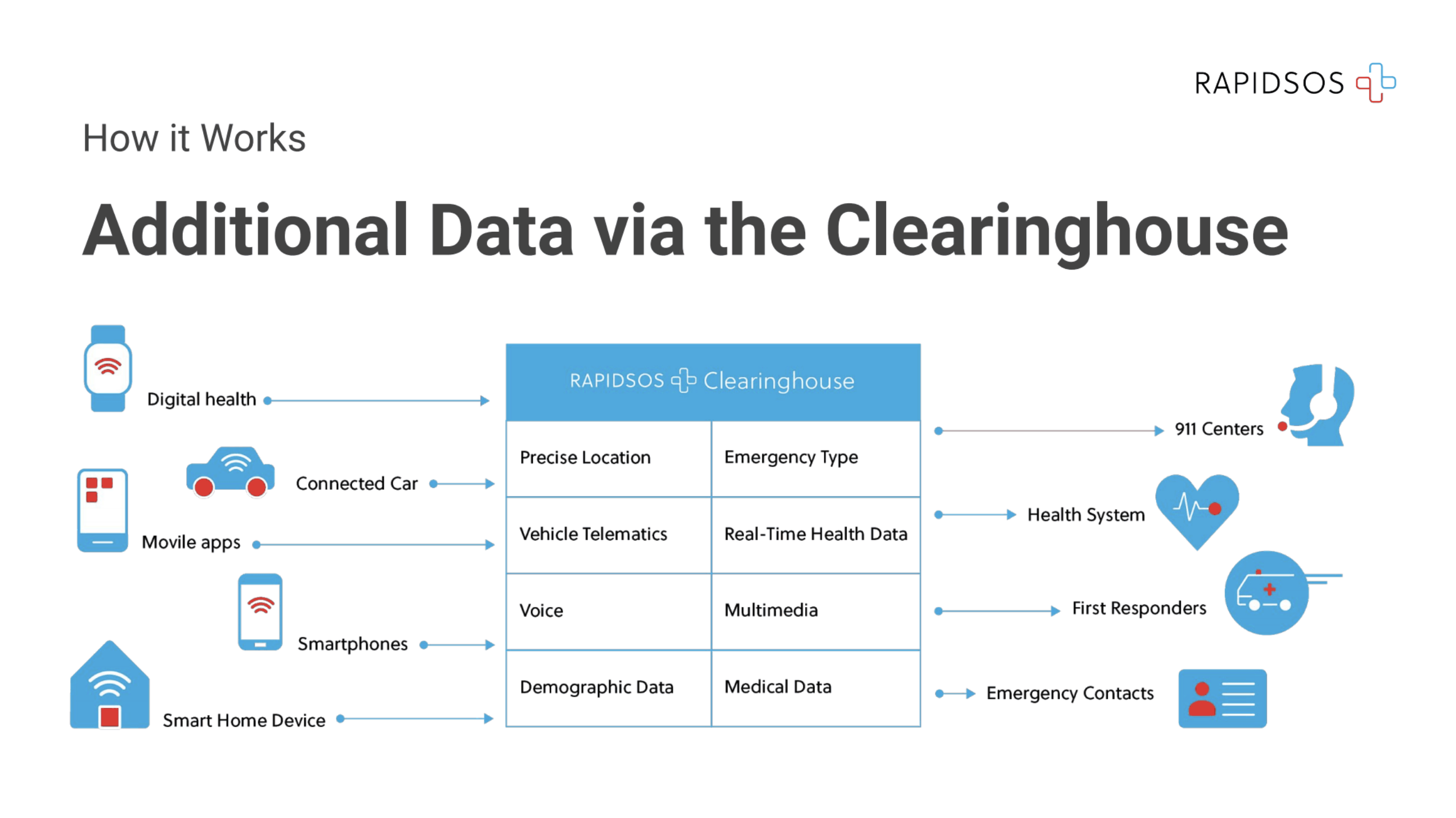

RapidSOS Portal

Through the RapidSOS Portal, OPCD can access the RapidSOS Clearinghouse — a location and data repository that sends 911 centers a “payload” of data on the person calling.

RapidSOS, according to its website, can pull real-time caller location from iPhone and Android devices and mine “additional emergency data from mobile apps, wearables, connected vehicles, and smart homes. With RapidSOS Portal, telecommunicators have immediate access to all available data sources, such as Uber, MedicAlert and Sirius XM Connected Vehicle Services.”

RapidSOS acts as a middleman between 911 centers and private data owners. It signs deals with individual companies — including healthcare companies, home security systems, body camera manufacturers, in-car computer service providers and others — to provide personal data to 911 centers.

The RapidSOS service also provides precise caller locations. Traditionally, 911 centers have located cell phone callers based on information from wireless service providers, like cell phone tower information, which may only give a broad, sometimes miles-wide, range. NG911 technology like RapidSOS allows 911 centers to track the location of the phone itself, using the same precise location information that allows apps like Uber and Google Maps to track exactly where you are.

OPCD director Tyrell Morris said that the data from the RapidSOS Clearinghouse is only accessible to OPCD when someone makes a 911 call, not all the time. And the information is only available to OPCD call takers for 30 minutes after a call is made, he said.

Morris said that other than location information, no data from the RapidSOS Clearinghouse is added to the reports OPCD sends to law enforcement. However, an OPCD spokesman said there are no laws or regulations preventing them from doing so.

The service is provided to the city free of charge.

Carbyne

Carbyne was first used by OPCD early into the coronavirus pandemic. The software allows dispatchers to get more accurate caller location data and access a caller’s smartphone cameras with their permission. The software also allows OPCD to send voluntary questionnaires to callers and allows callers to communicate through texting or videochat.

The software stores “the rich data that a citizen has consented to share” — which can include their address, medical conditions, text chat transcripts and shared videos and photos — remotely via the cloud. That data “can be easily retrieved for evidence,” according to OPCD’s contract with Carbyne.

The software also analyzes 911 data to create “heat maps” and other reports that provide “the opportunity to proactively forecast resources,” according to the contract.

Rave Mobile Safety

Through Rave, OPCD has access to a feature called Smart911, which allows residents to voluntarily give information to the city’s 911 center, such as medical conditions and household makeup. A user’s information is only available when they, or “someone connected to their profile,” calls 911, according to the city’s website.

According to Rave’s website, the software allows call takers to “record notes about incoming calls, track the frequency of 9-1-1 calls from the caller’s phone number, and access an expanded view that displays both prior tickets and notes available for the caller’s phone number.”

Partnerships

Jefferson Parish Criminal Intelligence Center

The Criminal Intelligence Center, or CIC, is a multi-agency intelligence center created in 2011 and housed by the Jefferson’s Parish Sheriff’s Office in Metairie.

The CIC “is a collective effort from all involved agencies to better assist with tracking crime trends and sharing information across the metro area,” an NOPD spokesperson told The Lens in an email.

There are 21 participating law enforcement agencies, according to the Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office, including 17 state and local agencies and four federal agencies.

Local/state agencies: Jefferson Parish Sheriff's Office, New Orleans Police Department, Louisiana State Police, Kenner Police Department, Orleans Parish Sheriff's Office, Gretna Police Department, Plaquemines Parish Sheriff’s Office, Harahan Police Department, Mandeville Police Department, St. Bernard Sheriff’s Office, St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office, Slidell Police Department, St. John the Baptist Parish Sheriff’s Office, St. Charles Parish Sheriff’s Office, East Jefferson Levee Police Department, Tangipahoa Parish Sheriff’s Office and the Louisiana Division of Probation and Parole.

Federal agencies: Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Naval Criminal Investigative Service, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

The NOPD spokesperson said that three NOPD detectives are currently stationed out of the CIC.

“The CIC is extremely important for current-day NOPD investigations, and it also helps often with day-to-day criminal investigations not only within the City of New Orleans, but its surrounding parishes as well,” the spokesperson said.

The spokesperson said that participating law enforcement agencies can access NOPD data through the partnership, including “search warrants, reports, documents, criminal investigations, video footage, body cameras, license plate readers, etc.”

The relationship between the law enforcement agencies is formally governed by a cooperative endeavor agreement, which was recently renewed by the City Council until 2024.

Violent Crime Abatement Investigation Team

The Violent Crime Abatement Investigation Team is an NOPD unit and partnership between the NOPD, FBI and the Louisiana State Police that utilizes intelligence technology and specialists from all three law enforcement agencies. The NOPD has engaged with other federal joint task forces in the past.

Safecam

Safecam is a registry of privately owned security cameras created through a partnership between the city and the New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation. The city later rolled out Safecam Platinum, which allows residents and businesses to stream live footage from their own security cameras to the RTCC. But the Safecam registry is still maintained for officers to retrieve archived footage. That registry included 6,000 cameras as of December 2018. But according to an RTCC spokesperson, that registry was lost due to a 2019 cyberattack. Since then, the city has rebuilt the registry and is currently at “roughly 1,000” cameras, according to the spokesperson.

Project NOLA

The New Orleans based nonprofit Project NOLA — run by former police officer and district attorney investigator Bryan Lagarde — helps set up and manage surveillance cameras, license plate readers and gunshot detectors across the country, including in New Orleans; Natchez, Mississippi and Woodbury, New Jersey.

Live streams from most of the cameras across the country stream to a private real time crime center Lagarde runs on the University of New Orleans campus, he told The Lens. That includes over 4,000 cameras in Orleans Parish.

Lagarde said that in every other city besides New Orleans, Project NOLA has a formal relationship with the police that allows them to directly access the live footage from their jurisdiction.

“With the exception of the NOPD, Project NOLA has helped create dozens of local and regional RTCC's where local law enforcement may monitor crime camera video in their area,” Lagarde said. “Crime camera video is streamed via the internet to our private data center at UNO, where video is recorded. Project NOLA provides local police and sheriff's offices special Video Management Software, free of charge, so that authorized officers, detectives, dispatchers, etc. may access Project NOLA Crime Camera feeds in their area.”

But in New Orleans, NOPD detectives have to request footage through a form on the Project NOLA website. In addition, Lagarde said Project NOLA will “proactively reach out to NOPD officers to advise them of crimes in progress, when we have eyes on a known subject wanted for a major crime, etc.”

“Since 2010, Project NOLA has repeatedly offered its services to the New Orleans Mayor's Office and the Mayor's Office of Homeland Security, to no avail,” he said. “Regrettably, the mayor has no interest with entering into a formal relationship with Project NOLA.”

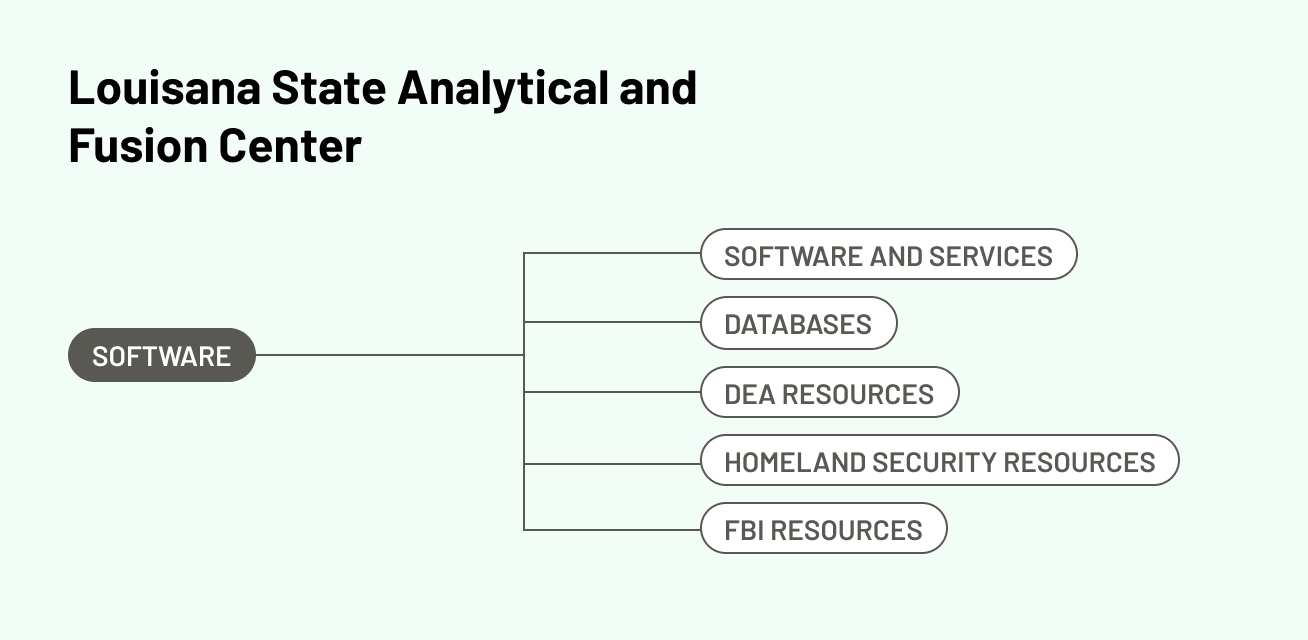

Louisiana State Analytical and Fusion Center

The Louisiana State Analytical and Fusion Exchange, or Fusion Center, in Baton Rouge is one of 80 similar fusion centers located in every state in the country, as well as three US territories.

Created in the wake of 9/11 with funding from the federal government, fusion centers are one of the primary conduits for intelligence sharing between local, state and federal law enforcement. Police departments like the NOPD send their data to these fusion centers and in return gain access to massive datasets and advanced intelligence tools used by federal agencies like the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security.

To access Fusion Center tools, NOPD detectives have to fill out a form requesting certain intelligence services. The following list of tools and databases is based on a 2020 version of the request form as well as a 2018 document produced by the Fusion Center that explains all of its resources. The list below highlights some of the most powerful and interesting tools from the 2018 document, but it doesn’t include all of them.

The Lens submitted a public records request to the Fusion Center for all of its active contracts and agreements. An initial letter from the Louisiana State Police denied the request on the basis it was “too broad and overburdensome.”

When The Lens questioned why it would be overburdensome for an office to collect its own contracts, the State Police sent a follow up letter.

“LA-SAFE compiled and reviewed the records responsive to your request,” the letter said. “After reviewing those records, we have confirmed that the process is overly burdensome. However, at this point, after having reviewed these records, your public records request is denied as the records you seek pertain to security procedures, investigative training information or aids, investigative techniques, and investigative technical equipment instructions.”

The Lens requested further clarification. In a phone call, Louisiana State Police Captain Nick Manale told The Lens that the Fusion Center is party to 119 contracts and other agreements. He said that the state police would not release the majority of those contracts due to an exemption in the state's Public Record Law for certain law enforcement documents.

“Pretty much everything the Fusion Center does that is related to their intelligence gathering or protocols is going to be exempt, because that's the nature of their business,” he said.

The Lens asked if they could send all contracts and agreements that were not exempted due to law enforcement sensitivity.

“The hard part is that we'd have to go through each one,” Manale said. “We'd have to ask them to pull those contracts and then look through them.”

The ACLU of Louisiana has also had trouble getting records from the office, and in February, it sued the Fusion Center, claiming it was in violation of the state's Public Records Law. In March, Louisiana State Rep. Charles Owen, Republican of Rosepine, filed a bill that would exempt the Fusion Center from the Public Records Law. But the bill was deferred and did not reach a full committee vote before the end of the 2021 legislative session.

Software and services

Facial recognition

A recent lawsuit from the ACLU of Louisiana against the State Police alleges that the facial recognition software used at the Fusion Center may have come from French company Idemia.

ADACS

Fusion Center Description: “A phone call analysis tool providing for the collection, analysis and distribution of intercepted communications. User defined analytical reports and graphical analysis tools for charting, timelines, frequency graphics and GIS location mapping are available.”

It appears to be a product by Virginia-based Sytech called the Advanced Digital/Audio Collection System, which provides, according to the company’s website, “the ability to intercept, track, record, and analyze switch-based voice, video, and data transmissions from Verizon, AT&T, Sprint Nextel, T-Mobile and many other national and international service providers.”

ROCIC (Regional Organized Crime Information Center)

The ROCIC is one of six regional centers that make up a federally funded program called the Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS) Program. According to the Fusion Center, it “offers a variety of services to criminal justice member agencies, including: A centralized criminal justice database with connectivity among centers and nationwide search ability, analysis of investigative data, specialized investigative equipment for loan, technical assistance, training, and telecommunications system access.”

Databases

Louisiana State Police Incident Reporting System

The Louisiana State Police internal database that houses all Bureau of Investigation reports and the Patrol Division’s field interview card entries.

MOTION

Fusion Center description: “New Orleans Police Department’s internal database for law enforcement information that provides information such as criminal history, wants and warrants, and police reports.”

Louisiana State Police License Plate Reader system

The Louisiana State Police have 35 license plate readers installed around the state, according to the 2018 Fusion Center document.

CLEAR from Thomson Reuters

Fusion Center description: “A comprehensive check of various public records, to include business associated with a subject, relatives or associated, telephone numbers (some of which may be unlisted or cellular numbers) and professional licenses.”

According to reporting from The Washington Post, CLEAR provides access to records from utility companies (including electricity, internet, water and cable providers) in every state and several territories that provide 400 million names, addresses and service records as well as “billions of records related to people’s employment, housing, credit reports, criminal histories and vehicle registrations.”

Drug Enforcement Administration Resources

The US Drug Enforcement Agency’s El Paso Intelligence Center (EPIC)

Fusion Center description: “A hub that focuses and assists in the identification of drug traffickers and alien traffickers along the U.S. / Mexico border and is run jointly by the DEA and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.”

NADDIS Narcotics and Dangerous Drug Information System

Fusion Center description: “Searches DEA past and present cases and provides contact information for the case agent.”

U.S. Department of Homeland Security and Department of State resources

Homeland Security Information Network

Fusion Center description: “A comprehensive, nationally secure and trusted web-based platform able to facilitate sensitive but unclassified (SBU) information sharing and collaboration between federal, state, local, tribal, private sector, and international partners.”

Customs and Border Patrol Central Index System

Fusion Center description: “The Central Index contains data on lawful permanent residents, naturalized citizens, violators of immigration laws, aliens with Employment Authorization Document (EAD) information, and others on whom DHS components have opened alien files or in whom they have a special interest. CIS provides several major capabilities, including searching the alien database by multiple criteria and displaying summary level data on the alien.”

Department of State Consular Consolidated Database:

Fusion Center description: “A Department of State database that holds all of the current and archived data from all of the Consular Affairs port databases around the world. This includes application and biometric data on immigrant and non-immigrant visa applicants, as well as past violators or subjects of consular lookouts.”

Automated Targeting System:

Fusion Center Description: “The module used at all U.S. airports receiving international flights to evaluate international passengers prior to arrival.”

According to DHS, it is a “decision support tool that compares traveler, cargo, and conveyance information against law enforcement, intelligence, and other enforcement data using risk-based scenarios and assessments.”

ENFORCE (Enforcement Case Tracking System)

Fusion Center Description: “Database used to process illegal aliens and record information relating to other enforcement actions. This system generates reports summarizing operations, identifies deportable aliens located by country of citizenship; summarized inspection and investigation results and records seizures of controlled substances and other assets and materials.”

Image Search and Retrieval System (ISRS)

Fusion Center Description: “A web-based image storage and retrieval system that contains photos, fingerprints, and signatures of all persons issued a resident alien or border crossing card. Data in ISRS may be searched by name, alien number, country of birth, or card serial number.”

Federal Bureau of Investigation resources

National Crime Information Center

Fusion Center description: “The United States central database for tracking crime-related information and is maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division. Data is received from federal, state, local and tribal law enforcement agencies, railroad police, and non-law law enforcement agencies such as state and federal motor vehicle registration and licensing authorities.”

This includes access to the FBI’s Interstate Identification Index, according to the Fusion Center documents.

N-DEx (National Data Exchange)

Fusion Center description: “A criminal justice information sharing system that provides nationwide connectivity to disparate local, state, tribal, and federal systems for the exchange of information. It provides law enforcement agencies with a powerful new investigative tool to search, link, analyze, and share information, e.g., incident and case reports, on a national basis.”

EGUARDIAN

Fusion Center description: “An unclassified version of the FBI’S Guardian program that provides a suspicious activity reporting system. … The system facilitates situational awareness with respect to potential terrorist activity.”

The Law Enforcement Enterprise Portal (LEEP)

Fusion Center description: “An internet system that is accredited and approved by the FBI for sensitive but unclassified information. LEEP is used to support investigative operations, send notifications and alerts, and provide an avenue to remotely access other law enforcement and intelligence systems and resources.”

- Project concept and production by Caroline Sinders and Michael Isaac Stein

- Writing, research and reporting by Michael Isaac Stein

- Creative direction, research and design by Caroline Sinders

- Data visualization, research and graphic design by Winnie Yoe

- Web development and technical guidance by Annabel Church and Thomas Thoren

- Editorial support by The Lens

- Project funded by the Fund for Investigative Journalism