Safety

Does surveillance make us safer?

Clint Carter was suffering from diabetic nerve pain and waiting for a ride to the hospital when he was arrested in June 2018, he told The Lens later that year during a phone call from the Avoyelles Correctional Center in Cottonport, about three hours northwest of New Orleans.

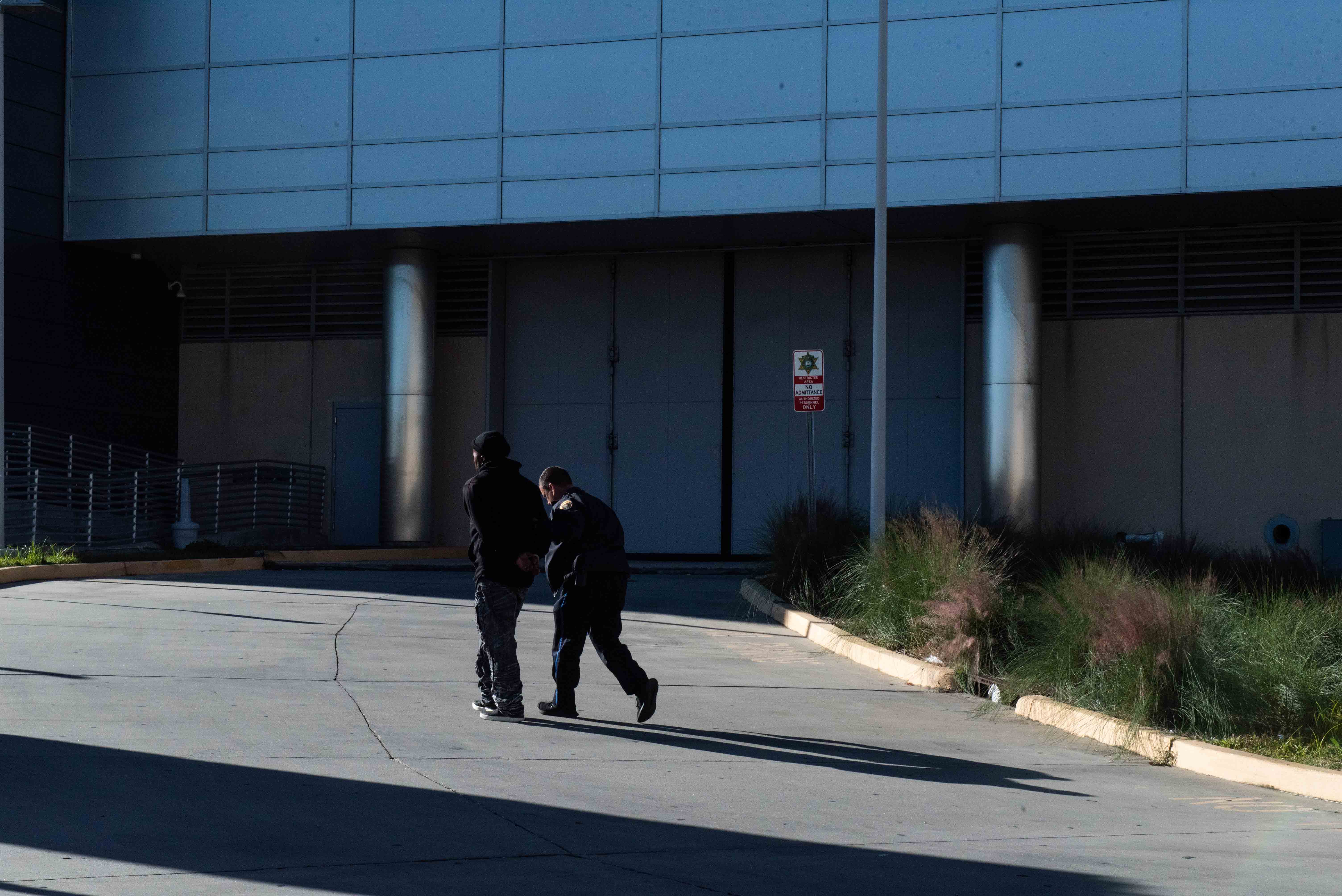

Standing with a few friends in Central City, he wasn’t aware that one of the city’s hundreds of surveillance cameras was actively zooming in and tracking him from one-and-a-half football fields away. The New Orleans Police Department suspected that Carter was selling heroin, and was using the camera to coordinate a drug bust.

The city has claimed that the camera system is “complaint-based,” meaning the police only search through footage after a crime is reported, rather than monitor the feeds in real time in anticipation of one. But the Carter arrest, and others, suggest that isn’t entirely true.

Surveillance footage of the arrest shows three NOPD SUVs swarm Carter, immediately put him in handcuffs and search him.

“No narcotics were recovered in the vicinity,” the police report said.

The police didn’t find any drugs, but they did find brass knuckles.

Carter was on parole at the time. He had been released from prison five months earlier after serving a year on a cocaine possession charge — one of three drug possession convictions over the prior two decades that resulted in prison sentences totaling 16 years. Carter struggled with addiction, his aunt, Dorothy Carter, told The Lens in an interview earlier this year.

Part of Carter’s parole agreement was that he refrain from carrying “dangerous weapons,” which includes brass knuckles, the police report said. Carter told The Lens that the brass knuckles belonged to a friend, who handed them to him just moments before the police showed up — a claim that appears to be corroborated by the surveillance footage.

Carter was booked on two charges: illegally carrying a weapon and trespassing. The trespassing charge came “per request of the property owner.” But the address at which Carter was supposedly trespassing is across the street from where he was standing when he was arrested. In the surveillance footage, he never approaches the house in question. And his lawyer, Laura Bixby, told The Lens in 2018 that during the trial, the officers admitted that the property owner never made a complaint in the first place.

“I’ve been living on them blocks all my life, I never had a problem with none of the neighbors or nobody in that neighborhood,” Carter told The Lens. “So they was lying from the get go.”

Following his arrest, the police took Carter to the hospital after he complained about chest pain, according to the police report. There, he was booked on a third charge — simple assault, based on a dispute over whether Carter could cover himself with a blanket. According to the report, Carter allegedly swung his hand around and threatened the officer but did not make physical contact with him. At the time, Carter was handcuffed to a hospital bed, and the officer was standing five feet away, according to the police report.

Carter was found not guilty of all three charges in November 2018. But the new arrest was a violation of his parole agreement. Carter was entitled to a hearing with the state parole board to address the alleged violation. But according to Carter and his attorney, his parole officer encouraged him to waive that right, saying he would only serve 15 days in jail if he did.

“His parole officer told him to just admit to the violation because it would just be a 15-day technical,” Bixby said. “And she admitted that to me on the phone. She later, after he signed that, changed her mind.”

Instead of a brief 15-day jail stay, Carter’s parole was revoked completely, and he was sent back to prison.

“I feel like I ain’t supposed to be in jail right now,” Carter told The Lens in 2018. “I’m doing time for nothing.”

Carter was released from prison in January 2019, six months after the arrest, according to the Louisiana Department of Corrections. He died in September 2020 of a heart attack, according to Dorothy Carter.

Asked in December 2018 how he felt about the city’s expanding surveillance network, he said he understood the need to fight back against murder and violence, but still felt nervous by the prospect of returning to a heavily surveilled city.

“You’ve got the officers using the cameras for the wrong reasons. Man, it’s just, I don’t know. I gotta go back to New Orleans. So I gotta go back and face that.”

Only a tool

Both supporters and opponents of the city’s rapidly expanding police surveillance capabilities often offer a similar argument: The technology enhances the police’s ability to do what it’s already doing.

“The technology is only a tool,” Rafael Goyeneche, president of the New Orleans Metropolitan Crime Commission, told The Lens.

Goyeneche, a former prosecutor, focused on how these tools can help police stop some of the most serious and urgent crimes, like tracking a kidnapper with license plate readers, coordinating a response to an active shooter with crime cameras or attempting to identify violent gang members with a social network mapping algorithm.

New Orleans has a long, tragic history with gun violence. For years it was ranked the nation’s “murder capital” among major cities, and continues to rank as one of the top five highest murder rates year after year.

But the city is also notorious for police abuse and corruption. And critics worry that increased surveillance will do more to amplify the latter problem than alleviate the former.

“We all want our homes and our families to be safe,” said Dee Dee Green, an organizer with Eye On Surveillance, a New Orleans privacy advocacy group. “This idea that we need policing and surveillance tools to keep us safe, that security blanket is sold to all of us. For some people that's a reality, for others of us it's not.”

Ursula Price, the former deputy director of New Orleans’ civilian oversight agency, the Office of the Independent Police Monitor, told The Lens that providing powerful tools to the current criminal justice system is just “making oppression more efficient.”

“The police department has established itself as being untrustworthy,” Price said. “We have ample evidence that the criminal justice system in Louisiana is dismally structured. We incarcerate the most people for a reason. We have the most overturned convictions for a reason. This is a horrible idea, to equip police departments we know are abusive with this kind of power.”

Price is hardly alone in her distrust of the U.S. criminal justice system. An Associated Press poll from last year found that almost all Americans believe the criminal justice system needs to be changed, and that a large majority believe that major changes or a complete overhaul is necessary.

Marvin Arnold, an organizer with Eye on Surveillance, argued that modern surveillance tools are doing harm by adding power to an already harmful system.

“We've seen people like Clint Carter targeted by surveillance, locked up in jail and unable to advocate for himself … when he was falsely and wrongly detained and imprisoned,” Arnold told The Lens. “These issues are here today and already harming people.”

New Orleans city officials have sometimes pitched the crime cameras as a way to increase fairness all around — not just to prove people’s guilt, but to prove their innocence as well. But defense attorneys say that simply isn’t how it works.

“The feeds from the Real Time Crime Center and the body cams go to the government,” said Colin Reingold, who worked as litigation director for the Orleans Public Defenders before recently moving to a position at the Promise of Justice Initiative, a New Orleans-based nonprofit that focuses on criminal justice reform.

“That means that when the government finds it useful to prove someone guilty, they have it at their fingertips. It is much more difficult for a defense attorney to get access to that same material when it could prove beneficial to the defense.”

At the time of Carter's arrest, defense attorneys didn’t even know where the cameras were installed. The case led Bixby to sue the city for access to a map of the crime cameras. She eventually won the case and the city now maintains an online camera map.

But the system is still far from equitable, Reingold argued, because the footage is deleted after 30 days unless flagged by the city, meaning footage can be deleted before a defendant even knows to request it.

“If they have an alibi, they don't know to ask the Real Time Crime Center to pull the video,” Reingold said. “Unless we're going to create a policy that all footage is retained indefinitely, then there's always going to be an advantage for the police who are doing investigations, who know they're doing investigations, rather than defendants who don't know they're under investigation and don't know what footage to ask for. I don’t know if there's a solution for that.”

Surveillance critics argue these tools exacerbate systemic problems in the criminal justice system. On top of that, they argue that crime cameras and massive government databases are ripe for individual abuse as well.

In 2014, a police camera operator in Northern Ireland was convicted of voyeurism after spying on a woman through her apartment windows for nearly a month. An officer in Washington D.C. was sentenced to prison in 2003 for an extortion scheme in which he collected license plate numbers of gay bar patrons and used police databases to find out who they were and whether they were married. An investigation by the Detroit Free Press from 2001 found that over five years, 90 police officers had abused police databases to stalk women, threaten people and settle scores.

In New Orleans in 2018, police officers saw two crime cameras with NOPD logos installed on a public utility pole. But they weren’t owned by the city. A neighbor told the police the camera was privately owned by Jeff Burkhardt — the vice president of the city’s primary surveillance camera contractor, Active Solutions.

Burkhardt used to own the house closest to the camera, before his wife took control of it the year prior in a separation of property agreement, according to court records. The day after The Lens contacted Burkhardt about the camera, it was gone. But the city never explained what the camera was doing there.

“It's not speculative,” said Brian Hofer, chair of the Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission. “There's been real world harm, real human rights violations.”

Do cameras reduce crime?

Some residents say they’re willing to accept the privacy intrusions and financial cost of the surveillance cameras if it means making a dent in the city’s stubborn violent crime rate. The problem, Arnold argued, is that there isn’t convincing evidence that they actually will.

“I just think there's really no evidence to point to our city being safer because of this.”

In 2019, a group of criminologists and researchers published a comprehensive review of 80 distinct studies on the effectiveness of surveillance camera programs. The study found that while surveillance cameras could lead to a reduction in drug, vehicle and property crimes, they didn’t appear to have any effect on violent crime.

“Public safety agencies combating violent crime problems may need to consider whether resources would be better allocated toward other crime prevention measures,” the study concluded.

The effect on property and vehicle crimes was also dependent on where the cameras were installed. The biggest impacts by far were observed in parking lots and public transportation systems, with smaller impacts in residential areas and no significant impacts in city centers.

The results also varied by country. While studies showed some effects on crime in the United Kingdom and South Korea, the 20 studies that focused on American camera systems found no significant impacts.

Aside from the direct deterrent effect of surveillance cameras, they can also help build better cases after a crime occurs. They therefore contribute to the overall, long-term strategy of deterring crime by arresting, indicting, convicting and sentencing those who break the law.

Incarceration as a deterrent continues to be the central crime fighting tool in the U.S., which boasts the highest known incarceration rate in the world. But there is a growing debate over that conventional wisdom, with some researchers suggesting that the U.S. carceral system doesn’t deter as much violence as is typically believed, or worse, actually increases violence in society overall.

Police reform and abolition advocates argue incarceration is inherently harmful and destabilizing for communities, and that spending billions of dollars on police and prisons every year carries the opportunity cost of not investing in services that address the core issues of crime, like poverty, healthcare, education and housing.

But pinpointing the exact causes of crime fluctuations is no easy task.

Since Hurricane Katrina in 2005, New Orleans’ violent crime and homicide rates have oscillated. Homicides fell to their lowest level in decades in 2019. But in 2020, New Orleans followed a national trend of spiking homicide rates that has continued into 2021.

In search of an explanation, some looked at how policing tactics changed in 2020. One theory suggested that crime went up due to the nationwide demonstrations in 2020 following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minnneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. According to the “Minneapolis Effect'' theory, the demonstrations diverted police attention from patrolling and made officers more weary of doing “proactive or officer-initiated'' policing tactics in the aftermath.

Others, meanwhile, argued the 2020 crime jump was further evidence that violence and law enforcement action aren’t as closely linked as the police would have you think.

“We have this narrative that our police and our carceral systems are preventing this issue, but actually if you see what the pandemic has brought us, if you've seen the fallout from this pandemic and the instability in people's lives, you'll see that is actually the problem,” said Sarah Omojola, the associate director of the Vera Institute of Justice’s New Orleans office, at a March community forum.

New Orleans crime data analyst Jeff Asher tried to untangle this “complex stew of forces” in an article he co-wrote for The Intercept. He didn’t find convincing evidence that the murder rate went up due to the so-called “Minneapolis Effect,” although the article did say that increased distrust of the police may have played a role.

There was evidence that violence got worse as the year went on, the article said, suggesting that “pandemic fatigue alongside the worsening economic and psychological strain of life under lockdown” is a culprit of the increased violence, particularly in the latter half of the year.

Increased gun sales could have also facilitated the rise, the article said.

The “high risk” population

Along with the mass surveillance of public spaces, new surveillance tools are allowing cities to closely monitor targeted individuals and predict individual criminal risk.

In 2012, then-New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu launched an anti-violence program that brought together hundreds of suspected gang members for “interventions” at the Orleans Parish Criminal District Court, where they were confronted by local, state and federal law enforcement.

They were given a choice: Engage with social programs or prepare for swift police action and harsh prosecution if you commit another crime.

“We know who you are. We know who your friends are. We know where you go. We know everything about you,” Landrieu said in 2012 after the first call-in.

It was later revealed that the city was identifying people for the interventions using a controversial software from Palantir, a major data mining company. New Orleans police used the software to analyze law enforcement data — such as arrest records, field interview cards and jail phone logs — to help identify alleged gang members and predict which residents had the highest risk of involvement in a gun crime.

Landrieu’s program was based on the theory — popularized by criminologist David Kennedy — that the bulk of urban gun violence is concentrated among a small portion of a city’s population, and that the people most likely to commit a gun crime are more or less the same people that are most likely to be victimized by one.

If you can identify that group, the theory goes, you can intervene before violence occurs. But it becomes much more complicated when you take that theory out of an academic setting and face the practical implications of the government labeling certain residents “high risk.”

In a 2019 paper in the New York University Law Review, researcher and attorney Rashida Richardson argued that the “predictive policing” algorithms implemented by police departments — including the Palantir software used in New Orleans — are inherently biased because they rely on “dirty data.”

Predictive policing software is largely based on law enforcement records. The problem, Richardson argued, is that police data is skewed by historically biased police practices that made Black people and people of color more frequent targets of stops, frisks, arrests and imprisonment by the police — more data points to imply potential criminal behavior.

In 2012, The Times-Picayune reported that one out of every seven Black men in New Orleans was either in prison, on parole or on probation.

“We already know the New Orleans Police Department has disproportionately targeted people of color in this community,” Price said. “And now we're equipping them with technology that is focused on those same communities. So we're just gonna continue seeing the same problem.”

Then there is the question of what happens to people after they’re labeled as “high risk.” Critics said Landreiu’s interventions were too heavily focused on the law enforcement side. And some doubted that the city could even offer the social services necessary to effectively intervene in someone’s life, let alone fast enough to outpace the consequences of enhanced surveillance and prosecution.

A 2015 American Society of Criminology report found that only 25 out of the 158 studied participants from Landrieu’s interventions actually received services.

The study found that compared to 14 peer cities, New Orleans saw a statistically significant drop in violent crime in 2013, the year after the call-ins first began, although the study didn’t claim to isolate the effect of the call-ins from the myriad other factors that affect crime rates.

Mayor LaToya Cantrell began work on a similar “high risk” identification program soon after taking office, but has sworn to make it more focused on “impactful social interventions” rather than law enforcement action.

Origins: ‘bad national headlines’

Landrieu wasn’t the first New Orleans mayor to try and set up a surveillance camera network.

In 2003, former-Mayor Ray Nagin vowed to set up 1,000 cameras across the city. But the program languished, mired by secrecy, ballooning costs, corruption and faulty technology. The city never installed more than 240 cameras, and had constant trouble keeping them working.

Allegations emerged in 2009 that the main contractor for the project had paid to send Nagin and his family on lavish trips to Hawaii, Jamaica and a Saints playoff game in Chicago. The city eventually abandoned the program, and Nagin was later sent to prison after being convicted on a slew of corruption charges, some of which stemmed from the crime camera program.

The city’s second attempt to create a crime camera network can be traced back to 2016, when high-profile shootings in the French Quarter triggered concerns about public safety and the potential negative impact on the city’s tourism industry — a major economic driver for New Orleans.

“Bad national headlines,” Ryan Berni said. “The tourism industry leaders were very concerned about the economic impact the continued shootings would have.”

Berni was a deputy mayor under Landrieu and played a key role in implementing the $40 million public safety plan. Berni now operates a consultancy firm that represents Landrieu and his nonprofit.

He said that the plan was driven by an overall “desire to secure the French Quarter” and a $23 million contribution from the city’s Convention Center — a publicly-funded, state-created body and a major institution in the tourism industry.

“All along, I've always thought that this investment has nothing to do with safety, but protecting the income that tourism brings in,” Green said.

Berni said the plan was also motivated by a 2017 terrorist attack on the Westminster Bridge in London that made the FBI nervous about Bourbon Street — the city’s most well-known tourism draw — as a potential target.

“Our priority in developing our crime reduction and homeland security plans was to increase public safety,” said a written statement from Landrieu. “It was also very important that we balanced those needs with privacy concerns from advocates, the public at large and victims.”

Berni pushed back on accusations that the Landrieu administration didn’t adequately engage with the community before installing the camera network. In fact, he said the plan only expanded outside of the French Quarter and into other residential neighborhoods after demands from residents and elected officials.

"In that process of engaging other elected officials and the public, there was a cry for ‘don't just put this investment in the French Quarter, we need this in crime hotspots all over the city,’ from residents, business leaders, community groups. So the scope of the public safety plan, while initially narrowly focused on securing the French Quarter, expanded to a kind of more citywide endeavor.”

City officials have consistently responded to criticisms about the disparate racial impact of police surveillance by pointing out that residents from all parts of the city, including majority Black neighborhoods that have been historically over-policed, have requested more crime cameras.

“It’s a complicated issue,” Price said.

Obviously, Price said, there are going to be varying opinions within any community. And she pointed out that many of the neighborhoods that have been historically over-policed and over-surveilled are the same neighborhoods that deal with the densest concentration of violent crime. She said that people exasperated and traumatized by violence haven’t traditionally had any viable recourse outside of law enforcement, given the lack of investment in alternatives.

“The folks more impacted by these problems, some of them are likely to be, if not pro-law enforcement, just want to see more law enforcement in their community, because that is the solution that has been given to us,” she said. “The problem is in this conversation, our sense of our options has been very limited on purpose. We've been told the only way is to harm people and their families by incarcerating them. That's the only way to prevent crime, that's the only way to have any just outcome after a crime. And that's just not true.”

Police reform

Berni said there is legitimate reason to be skeptical about local police surveillance. But he pointed out that the NOPD has been closely monitored under a federal consent decree since 2013, following a 2011 Department of Justice investigation that found routine civil rights infractions, biased policing and constitutional violations at the hands of NOPD officers.

“The New Orleans Police Department is probably more closely watched and more closely regulated on its interactions with individuals and its use of data and technology than anywhere else in the country. So I think it is a fair concern to have about how police would use information. I think in this particular instance here, it's unwarranted."

But the consent decree isn’t permanent, and a recent announcement from the court-appointed monitoring team indicated it could be ending in the next couple years.

“The real test of this consent decree isn't so much the next two years, it's the five years after the monitoring ends,” Goyeneche said.

Goyeneche pointed out that the NOPD had gone through a major overhaul effort in the 1990s when the department was marred by corruption and abuse scandals.

“After a couple years, the department fell back into their old ways of doing things,” he said. “Victory was declared. And we began to backslide.”

When the consent decree ends, the federally appointed monitoring team — the main oversight body keeping the department in check — will dissolve. The city will have to rely on its own local oversight agency — the Office of the Independent Police Monitor.

“That's really taken a back seat post-consent decree, because the federal monitors have basically been front and center reviewing all of this,” Goyeneche said. “But once the consent decree is terminated in New Orleans, that's going to be the primary responsibility of the Independent Police Monitor.”

Officials in the Office of Independent Police Monitor have consistently complained that they don’t have the access, power or resources to effectively provide oversight. Price said that the Independent Police Monitor had no idea about the city’s predictive Palantir software until six years after the city started using it.

“We learned from reading it in the news. No one in the city informed us we were getting involved with Palantir. Never once did we see any data in our oversight of the New Orleans Police Department that would indicate they had this kind of relationship. So we were totally in the dark.”

Not just the NOPD

While many New Orleans residents remain wary of the NOPD, most agree that the department is less corrupt, biased and abusive than when the consent decree began.

But there are also dozens of other law enforcement agencies operating in Orleans Parish that have access to NOPD data or surveillance tools, most of which don’t abide by all of the NOPD’s rules.

The NOPD recently adopted a new records management system that will be integrated “natively with the Louisiana State Police.” The records and advanced analytic tools will be available to any law enforcement agency in Orleans Parish, including the Levee District Police, university police departments, neighborhood security districts and other law enforcement agencies that don’t abide by the federal consent decree.

“Think about the amount of work and money that the city of New Orleans has put into reforming NOPD,” Price said. “And then we equip departments we know that don't meet our standards of constitutional rights or privacy with the same information we have. We're still leaving our people in danger.”

Recently, two security officers working for one of New Orleans’ neighborhood security districts were sued for pulling their guns on a group of black teenagers looking for a lost dog. Both officers were primarily employed by law enforcement agencies other than the NOPD — The Levee Board Police and the Housing Authority of New Orleans Police — and weren’t subject to NOPD policies or oversight under the consent decree. One of the officers was previously fired from the NOPD.

The Louisiana State Police, meanwhile, have faced consistent allegations of racism and abuse, and are currently facing a federal investigation into alleged attempts to cover up the circumstances surrounding the death of Ronald Greene during an arrest.

For undocumented immigrants, the central concern is data sharing with federal immigration authorities. During Landrieu’s administration, the NOPD created a policy that said officers couldn’t assist in immigration enforcement efforts in most situations. But the city is still party to a number of intelligence sharing arrangements that include federal agencies.

“Data sharing between local, state and federal law enforcement is incredibly dangerous,” New York privacy advocate and attorney Albert Fox Cahn said. “Something that really hasn't been appreciated as part of the sanctuary city movement is the need to prevent data transfers from state and local officials to the federal government.”

The Louisiana State Analytical and Fusion Exchange in Baton Rouge acts as the central vehicle for local and state law enforcement to share intelligence and data with each other and the federal government. The Fusion Center has a number of surveillance tools and databases available for qualifying law enforcement agencies. One of those databases is the NOPD’s internal records system.

The NOPD is also part of a regional intelligence-sharing partnership of 21 law enforcement agencies through the Jefferson Parish Criminal Intelligence Center. The participating agencies include 16 local police and sheriff's departments as well as six federal agencies, including ICE and Customs and Border Control.

Meanwhile the city’s Real Time Crime Center, which monitors the city’s cameras, doesn’t just serve the NOPD. The center is housed under the city’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, and it serves a long list of agencies including the FBI, the Louisiana State Police and the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office. (New Orleans’ homeland security office is a city office, separate from the federal Department of Homeland Security.)

The NOPD didn’t respond to questions about whether the department takes steps to prevent NOPD data being used for federal immigration enforcement through these various partnerships.

Rocío Aguilar is an organizer with the New Orleans immigrant advocacy group Congreso de Jornaleros, and she says that the city’s surveillance network, combined with an overall fear of immigration authorities, discourages some immigrants from getting involved in advocacy or seeking help from authorities.

“It makes people limit their activities with groups like Congreso, it makes them feel like they can't get involved,” she said through an interpreter. “It creates fear to go and look for the things we need to access. People are afraid, literally, to seek help because they ask, if I do seek help, how could that information be used against me in the future.”

Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams told The Lens he was already facing that problem since he took office in January.

“They're scared to come forward to report a crime that's been done to them because they're scared they'll get deported. I'm fighting that battle right now.”

Immigration advocates and attorneys claimed that under former-President Donald Trump, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security targeted immigration advocates for deportation and other harsh immigration enforcement measures.

“We're really concerned with the ways that developing surveillance technology has implications for all sorts of vectors of civic and political life,” said Chris Kaiser, advocacy director for the ACLU of Louisiana. “As we see proliferation of cameras and software like facial recognition in all public settings, we do erode the possibility of public anonymity. And when you do that, you make it really hard for people to freely associate and express themselves, participate in political life. And that has disproportionate effects on people who are already marginalized.”

- Project concept and production by Caroline Sinders and Michael Isaac Stein

- Writing, research and reporting by Michael Isaac Stein

- Creative direction, research and design by Caroline Sinders

- Data visualization, research and graphic design by Winnie Yoe

- Web development and technical guidance by Annabel Church and Thomas Thoren

- Editorial support by The Lens

- Project funded by the Fund for Investigative Journalism