The Cost of a Camera

New Orleans has spent millions on surveillance, but the full price tag is unclear.

The upfront cost of a single New Orleans surveillance camera ranges from $1,094 to $8,263, depending on their capabilities — like zoom, pan tilt and automatic movement tracking — according to city purchase orders and invoices obtained by The Lens.

But the price of the camera itself is only the beginning.

The cameras are put in metal encasements, often fitted with red and blue flashing lights, which cost $670 each. After that, the city has to buy equipment to mount the cameras ($52 -$157 per camera), a fee to connect them to the city’s video management software ($225 per camera) and labor costs of unpacking, assembling and mounting the cameras ($125 per hour). And there are other necessary costs for at least some of the cameras, like 15 foot cables for streetlight mounted cameras ($180 each) and memory cards ($98 to $313 each).

In 2019, officials from Mayor LaToya Cantrell's administration said that it cost approximately $9,200 to purchase and install each camera through its primary surveillance contractor, Active Solutions. The city assembles at least some cameras in-house as well, according to a 2019 budget presentation, bringing the cost down to $5,500 each.

But the initial installation expenses still pale in comparison to what the city will have to pay over time in annual costs, like annual licensing for the city’s video management system.

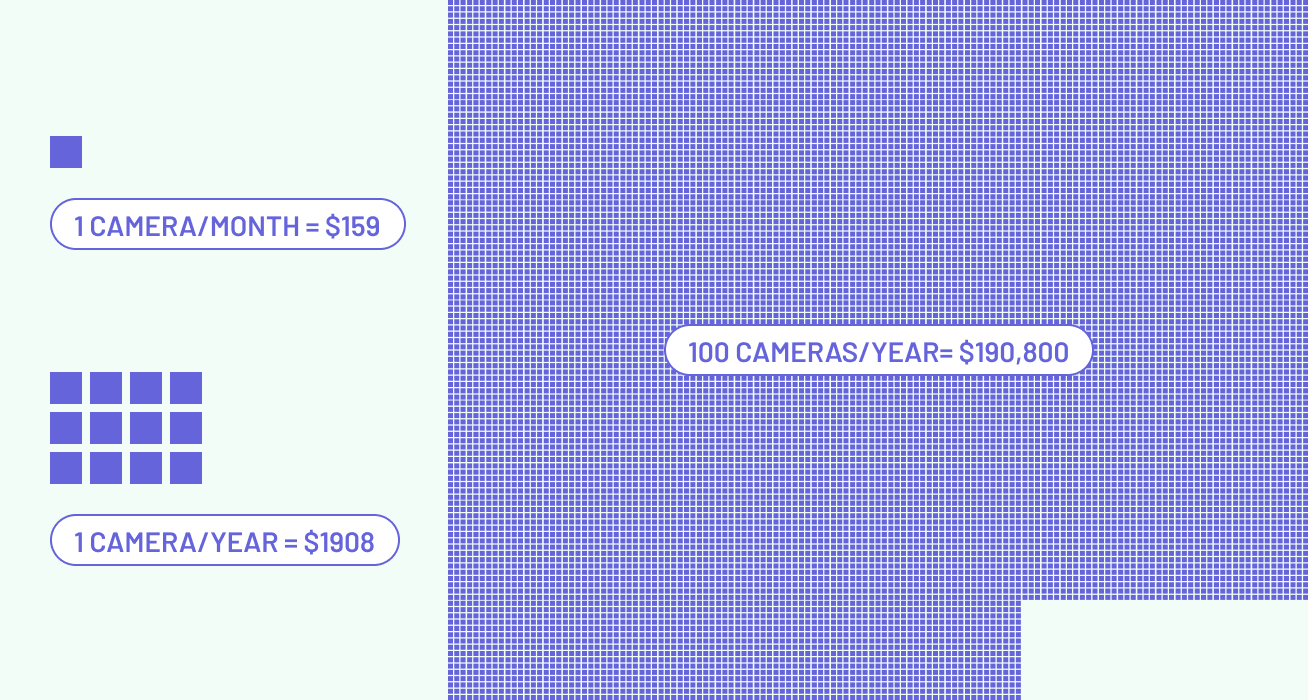

The biggest annual expense appears to be for WiFi. In order to beam live footage to the city’s Real Time Crime Center, each camera needs to be connected to the internet. Invoices show that internet costs through Cox Communications for a single camera are $159 a month, or $1,908 a year.

The city operated 555 of its own cameras as of January 2021, as well as 89 automatic license plate readers. If it were paying for a connection for each, the total would be well over $1 million per year.

But a lack of clarity from city officials and documents makes it difficult to know the true total. Ross Bourgeois, the administrator of the RTCC, said in a statement that not all the cameras were individually connected through Cox. He said that some were connected through fiber optic cables, but did not respond to questions about the annual cost of the fiber connectivity or how many cameras were connected through fiber.

Bourgeois also said that some cameras are close enough to share WiFi with other cameras or a nearby city-owned building. But he didn’t say how many. And the city ultimately ignored repeated questions from The Lens about the annual internet cost for the entire camera fleet.

The city also has to pay for annual expenses for the camera fleet as a whole, namely ongoing equipment maintenance and upgrades to make sure the system doesn’t fall into disrepair.

At a city budget hearing last year, Collin Arnold, director of the city’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, which runs the Real Time Crime Center, explained that the cameras need constant upkeep to continue working.

“I can’t really stress enough that the cameras are not this kind of set it and forget it thing,” Arnold said at the meeting. “If you don't maintain them, they won't work. So maintenance is a large part of what we’re doing.”

On top of maintaining the camera fleet, the Real Time Crime Center also has to pay for staff, office space, equipment and software required to actually utilize the footage through the Real Time Crime Center. The city estimated that just the initial renovation of the building housing the Real Time Crime Center cost $5 million.

'Force Multiplier'

The city has argued that the investment in the Real Time Crime Center pays dividends by acting as a “force multiplier” that can free officers from the time-consuming process of collecting and reviewing video evidence.

In late 2018, roughly a year after the RTCC first opened, the city said that the surveillance hub had saved 2,000 hours of “public safety manpower.” That’s equivalent to just under one year of work for a single police officer, or about $60,000 in non-overtime payroll costs.

Meanwhile, the city has spent millions on the RTCC, including $4.3 million in payroll costs for 26 employees who worked at the center between its opening in 2017 through July 2021. The annual payroll cost in 2020 alone was roughly $1.2 million.

While the city provided The Lens with comprehensive RTCC payroll data, The Lens faced much tougher obstacles trying to tally the other hardware, software and service costs associated with the RTCC.

Ultimately, The Lens was able to confirm $6.1 million in spending directly related to RTCC operations, based on purchase orders from Cox and the RTCC’s three biggest surveillance equipment and software vendors: Active Solutions, Motorola Solutions and LaTech.

Combined with RTCC payroll costs, The Lens confirmed $10.4 million in RTCC spending since 2017.

But that figure is all but certainly an inaccurate reflection of the RTCC’s actual costs. It was only based on purchase orders that had an explicit connection to the RTCC and that were reviewed by an RTCC spokesperson. The real total is likely much higher.

Incomplete, inaccurate records

The Lens’ year-long attempt to establish a total price tag for the city’s surveillance technology was ultimately stymied by a lack of reliable and complete accounting from officials.

The effort was thwarted by inaccurate and incomplete records provided by the city in response to public records requests, the city’s inability or unwillingness to explain how The Lens should interpret certain purchasing records and the city’s refusal to answer basic questions about the city’s surveillance spending.

The central issue was that even internally, the city doesn’t appear to track how much it spends on the RTCC.

The city has provided few public cost estimates for the RTCC, most of which came in 2017, before the center had even opened. The Times-Picayune reported in 2017 that the startup cost of the RTCC and camera system would include at least $18.5 million provided by the city’s publicly-owned and tax-funded convention center. That obviously doesn’t include the cost of the many expansions that have occurred since then.

The paper also reported that the estimated annual maintenance costs would be $3.8 million a year. The Lens asked Laura Mellem, spokesperson for the Office of Homeland Security, whether the $3.8 million cost estimate proved to be true. The Lens also asked if the office maintained an internal budget for the RTCC, or if she could provide a rough estimate for annual costs. She didn’t respond to any of those questions.

The Lens submitted a public records request for any city documents that contained a budget, spending estimate or spending records for the RTCC. The city told The Lens that there were no such city records.

The annual city-wide budget the mayor releases every year doesn't provide much insight either. The RTCC is part of the city’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness, which was budgeted for $39.6 million spending in the initial 2020 budget. But the mayor’s public budget documents don’t contain enough information to isolate RTCC spending.

The Lens also submitted a public records request for invoices and purchase orders related to the RTCC, but the city informed The Lens that RTCC expenditures couldn’t be isolated from the rest of Homeland Security spending.

“Segregating the requested records would be time consuming and tedious, if not impossible,” said the response from the city’s Law Department.

The Lens then submitted a public records request for all invoices and purchase orders for the entire Office of Homeland Security for the years 2017 through 2020. In response, the city’s Law Department — which is responsible for fulfilling public records requests — released six different spreadsheets, but didn’t explain what the spreadsheets represented or how they should be interpreted.

After months of emails and phone calls trying to clarify how to most accurately interpret the documents, the Law Department forwarded the issue on to the Mayor’s Office and the Department of Finance to answer budget questions.

“At this point I think it’s best to have you get with the mayor’s communications team which can get your questions answered, or put you directly in touch with someone who can answer your questions,” said an email from Deputy City Attorney Anita Curran to The Lens and the mayor’s communication office.

The Mayor’s Office never responded to Curran’s email or follow up emails from The Lens, leaving several open questions about how to accurately interpret the documents.

The Lens was able to use the Homeland Security documents and other sources to pinpoint the city’s primary surveillance contractors. The Lens then submitted public records requests for more than a dozen companies from 2017 through 2020, in hopes of getting more comprehensible data and to ensure there weren’t surveillance purchases made outside the Office of Homeland Security.

But the documents produced by the city in response were clearly inaccurate, in some cases repeating single purchase orders several times. When The Lens pointed out the mistakes in the documents, the city admitted it incorrectly compiled the information.

According to Curran, city employees trying to compile the purchase records faced difficulties dealing with documents that were stored in an old records system that the city replaced in June 2019. That system is apparently no longer fully functional.

“I learned that our ITI team still struggles with how to effectively interpret the data from this legacy system now that the application is no longer functioning and we just have the database remaining,” Curran said in an email. “The individual who oversees this database for ITI does not have a firm understanding of the data from a business perspective.”

The city compiled yet another set of records. But some of the new documents were missing purchase orders that had appeared in the first set of documents. After The Lens pointed that out, the city compiled a third set of records. Even then, problems persisted.

For example, the new records showed that the city as a whole issued $1.1 million in purchase orders for Active Solutions from 2017 through 2020. However, a separate document — provided in response to an earlier request — showed $2.6 million in Active Solutions purchase orders just within the Office of Homeland Security over that same period.

For three of the requested companies — Avexon, Sirennet and Tomba Communications — the city told The Lens it wasn’t in possession of any purchase orders or invoices, even though the documents detailing Homeland Security purchases showed thousands of dollars in purchase orders at those companies.

The spreadsheets provided by the city also don’t include enough information to isolate RTCC costs. Some spreadsheets only have vague descriptions for equipment, like cables and monitors, that don’t specify whether they were used for crime cameras or something else. Other spreadsheets don’t have line-item descriptions at all.

The Lens similarly couldn’t isolate general RTCC costs — like office supplies, energy bills and janitorial services — from the rest of the Homeland Security budget.

- Project concept and production by Caroline Sinders and Michael Isaac Stein

- Writing, research and reporting by Michael Isaac Stein

- Creative direction, research and design by Caroline Sinders

- Data visualization, research and graphic design by Winnie Yoe

- Web development and technical guidance by Annabel Church and Thomas Thoren

- Editorial support by The Lens

- Project funded by the Fund for Investigative Journalism