Neighborhoods Watched

The rise of urban mass surveillance

New Orleans has spent millions to expand its police surveillance powers in recent years, providing the city with an unprecedented ability to monitor public spaces and track individuals.

Similar mass surveillance systems have rapidly spread to cities across the US in the last two decades, for the most part without any formal oversight or local regulation.

As a result, the public is often left in the dark about what tools and techniques the police use to spy on them.

In partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism, The Lens has spent the past year obtaining and reviewing thousands of city documents to get a snapshot of New Orleans' current surveillance apparatus and the rapid, largely unchecked nature of its growth.

“What’s up with these cameras?”

That’s what Dee Dee Green remembers thinking the first time she saw one of New Orleans’ police surveillance cameras in 2018, flashing red and blue lights over a community garden she manages in the city’s Hollygrove neighborhood.

“There was no real community engagement around these cameras, it just happened,” said Green, a member of the local anti-surveillance coalition Eye on Surveillance. “We noticed a camera above our garden space and wanted to begin investigating.”

The cameras began popping up across town in late 2017 as part of a $40 million public safety plan that also included a fleet of license plate readers and a state-of-the-art surveillance hub called the Real Time Crime Center. Since then, local advocates like Green have been working to track and expose the city’s surveillance capabilities.

But it hasn’t been easy.

New Orleans’ surveillance apparatus isn’t so much a comprehensive system as it is a sprawling, decentralized and constantly changing patchwork of tools maintained by various city departments, semi-independent agencies, private nonprofits and federal and state law enforcement.

“It's sort of a Frankestein's monster,” said Bruce Hamilton, former senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Louisiana, who now works for the Southern Poverty Law Center. “I don’t think there's a grand plan.”

There is no consolidated “department of surveillance” in New Orleans, no single venue where residents like Green can go to learn more. Nor is there a formal regulatory structure for internal tracking, public disclosure or approval for surveillance or data collection technology.

The city makes it even harder to navigate that labyrinth by consistently refusing or failing to give accurate information to the public, privacy advocates told The Lens.

“The status quo is that the government is really free to acquire, deploy, expand existing surveillance technology outside of public view, without public input and without oversight,” said Chris Kaiser, the advocacy director for the ACLU of Louisiana and member of Eye on Surveillance, at a New Orleans City Council hearing last year.

“Often, as a result, we really don't know what's out there.”

Despite all the muddiness, the city drew one clear line in the sand early into the camera program: it wouldn’t use facial recognition.

For over two years, officials repeatedly assured the public of that voluntary restriction. It’s even written in bold on the city’s website and included in the privacy policy for the Real Time Crime Center.

It was a rare point of clarity in an otherwise opaque surveillance system. Except it wasn’t true.

In November 2020, the NOPD admitted that detectives had been using facial recognition since at least 2018. The department justified its previous denials by arguing that the city didn’t own the software itself. Instead, NOPD investigators were accessing it through the Louisiana State Analytics and Fusion Exchange — one of 82 “fusion centers” across all 50 states that make up a vast, federally funded intelligence and data sharing network.

“It's a distinction without a difference,” Hamilton said. “NOPD is still using the technology, just getting someone else to do the dirty work.”

And that wasn’t the first time the city was accused of shrouding its surveillance powers.

In 2018, an article from The Verge shocked many New Orleans residents when it revealed that the NOPD had quietly obtained an advanced analytic software — called Gotham — and used it to create a database listing the one percent of New Orleans residents with the highest perceived threat of committing a gun crime.

The software was made by Palantir — a data-mining company founded by billionaire Peter Thiel with early investment from the CIA’s venture capital branch. The NOPD had been using the software for six years by the time the practice was exposed by The Verge, which characterized it as a “predictive policing system.”

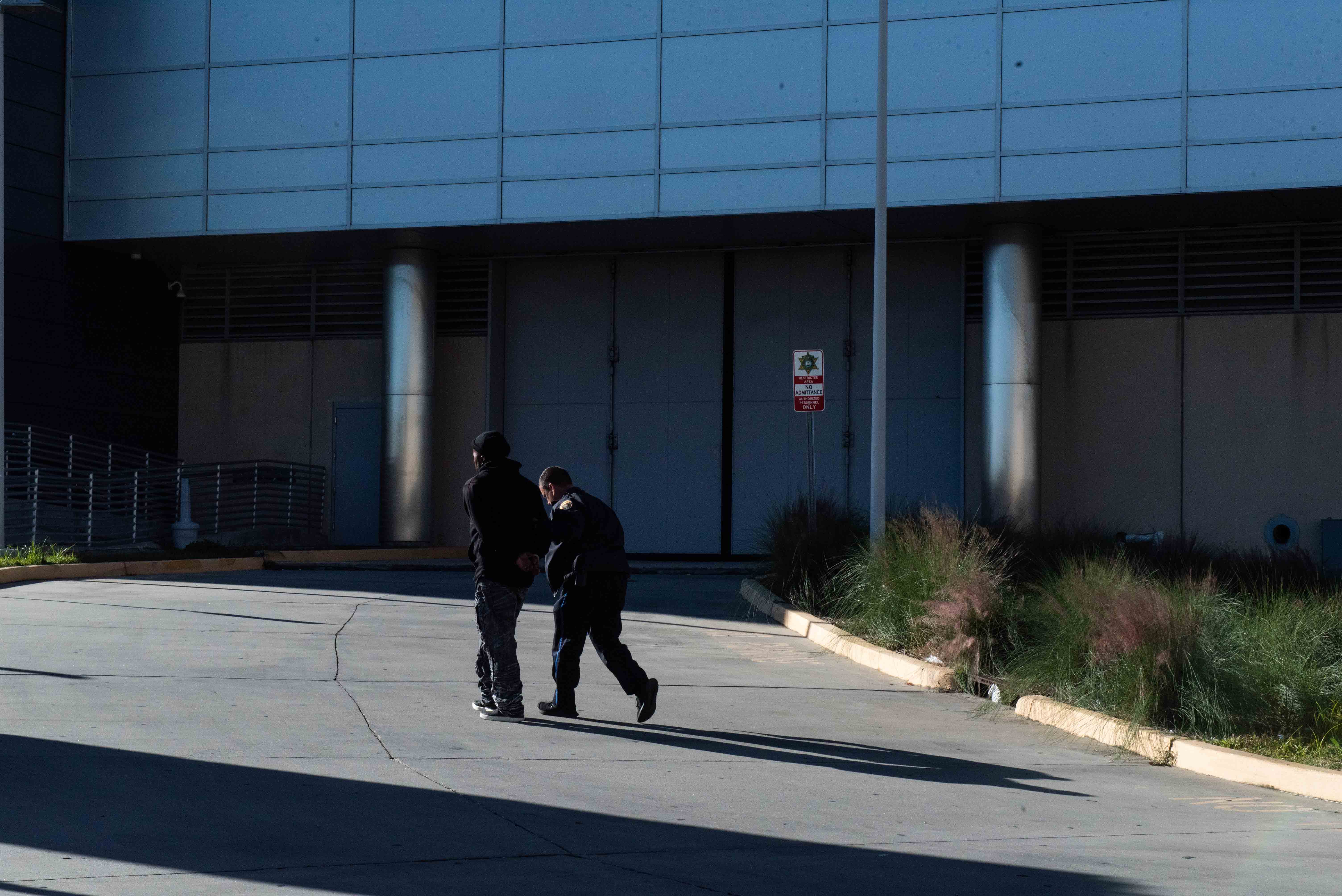

Starting in 2012, under former Mayor Mitch Landrieu, the city used Palantir’s Gotham software to identify and round up hundreds of potential gang-members for public safety “interventions” at the criminal court building, where they were informed that they and their friends were being closely watched and could face enhanced prosecution for future crimes.

"We know who you are. We know who your friends are. We know where you go. We know everything about you," Landrieu said after the first “intervention” in 2012.

Even getting basic information about the city’s surveillance arsenal can be an exhausting exercise. The city, for example, refused to release a map of its surveillance cameras for years until it was sued by an attorney from the Orleans Public Defenders Office with representation by the ACLU.

“The fact that we had to sue to get a map of publicly visible cameras I think just illustrates the kind of ridiculousness of the city claiming it has any type of transparency when it comes to surveillance,” Hamilton said.

The city ended up fighting the lawsuit all the way to the Louisiana Supreme Court before it was finally forced to turn over the camera locations in 2020.

“If transparency was anything more than just lip service, the city would have just said, ‘Here's the map,’ “ Hamilton said. “We shouldn't have had to fight for it.”

To Hamilton, the city’s record points to a clear conclusion: The public can’t trust City Hall to willingly and accurately inform them about the tools it uses to spy on them.

“They don't deserve our trust,” Hamilton said.

Over the past year, Cantrell’s office denied multiple interview requests for this project and ignored many of The Lens’ emailed questions regarding the city’s use, oversight of and investment in surveillance technology. The city also provided incomplete and inaccurate records in response to some of The Lens’ public records requests.

But a short written statement from a Cantrell spokesperson said that the Real Time Crime Center “is governed by a strict policy” and that “access is restricted and monitored.”

"The Crime Center has hosted many community groups for tours and has attended dozens of community meetings to provide information on the public safety camera program and to answer frequently asked questions. A map of camera locations is available on the website, along with a form for residents to submit camera location requests."

In a short statement, Landrieu told The Lens that his administration strived to balance public safety needs with privacy rights.

“You can have Constitutional policing and reduce crime,” Landrieu said. “It is possible to do both.”

Falling barriers to mass surveillance

Local mass surveillance systems have spread rapidly across the U.S. in the last two decades, from major cities like New York, to smaller ones like Birmingham, Alabama, all the way to towns with populations under 1,000.

“Some of those traditional checks and balances as far as budgeting are being circumvented and police departments are building huge arsenals of surveillance technology without any kind of engagement from lawmakers and without the awareness of the public,” said Nathan Sheard, the Associate Director of Community Organizing for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a digital privacy nonprofit.

Sheard said that historically, electronic mass surveillance systems were kept in check more by simple practicality than legal restrictions. Some technologies widely used by law enforcement today were traditionally too pricey for local police department budgets, while others were only recently invented.

But with cheaper technology and increased funding from the federal government, the prevalence of local mass surveillance systems has exploded. And some officials are now convinced that new legal restrictions are necessary to replace the falling barriers of cost and technology.

“It became abundantly clear that this was one of those places where technology was moving at the speed of light, but electeds and the government were moving at a snail's pace in terms of creating policy around it,” Orleans Parish District Attorney Jason Williams told The Lens. “I do think we're behind. I think most American cities are behind on this.”

Support The Lens

We are reader supported. Make an investment in The Lens, New Orleans’ first nonprofit investigative newsroom.

Donate NowWilliams, a former City Council member who ran for DA in 2020 as a progressive reformer, isn’t wholly opposed to new surveillance technology.

“There's a ton of technology I plan on using to prove cases over here at the DA's office,” he told The Lens. “If someone is using a weapon on city streets and it's picked up on a camera and I can access that camera, I'm going to use that as evidence.”

As a council member, he praised the city's 2017 surveillance expansion efforts, and specifically encouraged a controversial, and ultimately abandoned, plan to install infrared cameras that could see through people’s clothes to virtually check for weapons.

"Some of my liberal friends may say this is an infringement upon constitutional rights, but at the end of the day, what is more important than the safety of this community?” Williams said in 2017.

Williams was also an outspoken advocate of expanding data collection outside of the criminal justice system with “smart cities” technologies — an urban planning idea and multi-billion-dollar industry that encourages city governments to maximize data collection and analysis across all facets of civic life.

The more the city knows about its residents, the theory goes, the better it can serve them.

Analyzing traffic patterns can help reduce congestion. Monitoring residents’ energy usage can increase energy efficiency. Putting sensors in trash cans can help cut down on collection costs and prevent bin overflow. Other smart cities technologies have been credited with combatting the coronavirus pandemic, monitoring air quality and mitigating flooding risks.

Listen to a special podcast episode on this series, featuring Michael Isaac Stein and Caroline Sinders.

But that “smart” technology can also mean an exponential rise in the amount of data cities collect about their residents, and sometimes come with privacy implications that aren’t apparent when they’re first installed.

“Smart recycling bins” in London were turned off after it came out that they were mining data from passing smartphones. And the City of San Diego turned off the cameras in its “smart street lights” — originally installed as a way to study traffic patterns — after the public discovered the police started using them for criminal investigations.

Williams still believes in the potential of those technologies, but said his outlook “evolved” during his years on the City Council as he saw “how pervasive this technology can be in every facet of our lives without us actually having an intelligent conversation about whether or not we want all of this to happen.”

“People want the latest and greatest thing, but we're not educating ourselves on the negative ramifications of some of this technology,” he said.

In 2020, after he announced his run for DA, Williams began working with Eye on Surveillance to create a law setting restrictions and oversight measures for surveillance, only some of which were ultimately approved by the City Council.

“We gotta get in front of it,” Williams said. “Even if it's not here yet, we need to start having conversations about the best way to use these things and what we don’t want them to do ever.”

‘Fundamentally different’

Police surveillance is nothing new. Local police have long monitored public spaces — standing on a street corner, staking out a house or following a suspect through public streets. And they have long used data on residents, like arrest records and fingerprints, to solve cases.

Rafael Goyeneche, a former prosecutor and president of the Metropolitan Crime Commission, argues that new surveillance technologies are simply enhanced versions of what police have always done. He compared using facial recognition software to broadcasting a suspect photo and asking for citizen tips, both of which come with the risk of misidentification and racial bias.

“The technology is only a tool,” he told The Lens. “It doesn't mean that anyone's rights are being violated. It doesn’t mean the police are engaging in anything covert or constitutionally invalid.”

But Dave Maass, the head of investigations for the Electronic Frontier Foundation, argued that the technology at the fingertips of local law enforcement today isn’t just augmenting existing practices, it’s changing the nature of government surveillance and public anonymity altogether.

“If you look 20, 30, 40 years ago, when we're talking about surveillance, we're talking about a dude sitting in his car with binoculars looking at a particular person for a particular investigation,” Maass said. “We look at where we are now, we're talking about the advent of technologies that are collecting data on everyone all the time, regardless of whether you're suspected of being involved in a crime.”

“These are fundamentally different things,” he said.

In 2017, New Orleans began deploying mass amounts of surveillance hardware. The city's fleet of cameras and license plate readers has steadily grown every year since.

As of January 2021, the city had access to live video footage from 975 cameras. The city only directly owns 555 cameras, which are plotted on the map below.

The other 420 live video feeds come through a program called Safecam Platinum, which allows private residents and businesses to hook up their cameras to the city system.

This is a map of 48 participating Safecam Platinum businesses. The city refused to give the locations of the resident participants, citing privacy concerns.

The police also utilize archived footage from thousands of other private cameras that are registered with the city or with a private crime camera network, called Project NOLA, that works closely with the NOPD. The locations of those cameras are unknown.

The NOPD has also deployed 40 fixed license plate readers (LPRs), 10 mobile LPRs , 39 vehicle-mounted LPRs, 826 dashboard cameras and 1,383 body cameras, as of early 2021. The city denied a public records request for the fixed LPR locations.

The locations of the majority of the city's surveillance hardware are unknown, either because the city has refused to release the locations, or because they have no fixed location. The purple dots are theoretical representations of these unknown or moving locations.

New Orleans has steadily grown its surveillance hardware year after year. By late 2018, the Real Time Crime Center had access to a little over 300 live camera feeds. By the end of 2019, it was up to roughly 600. And by early 2021, there were nearly 1,000.

Meanwhile, in August, the city announced it was using $1 million in federal coronavirus relief aid to buy 150 to 160 more license plate readers.

But while the hardware is the most visible element of New Orleans’ surveillance network, the real power is on the other side of the lens — the advanced analytic software that mines, organizes and analyzes the footage.

“What we have now are algorithms that are watching all of the cameras all of the time, indexing everything in those cameras and then storing that potentially indefinitely,” Maass said.

The city started using this kind of algorithm in 2017 with a software called BriefCam. Instead of requiring officers to watch every second of every camera feed to find what they’re looking for, BriefCam watched it for them and broke down the footage into searchable components.

“BriefCam’s breakthrough technology detects, tracks, extracts and identifies people and objects from video, including; men, women, children, clothing, bags, vehicles, animals, size, color, speed, path, direction, dwell time, and more,” said a BriefCam press release announcing its work in New Orleans.

Once everything is broken down and cataloged, officers could easily comb through hours of footage in just minutes. (The city said it stopped using BriefCam in late 2019.)

This type of software is also used with body camera footage. Body cameras were adopted by the NOPD in 2014 as a police accountability measure, but they’re also a major tool in prosecutions.

In 2016, the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s Office started using software to mine and catalog audio and video captured by body cameras. The company announced its business with the New Orleans DA in a 2016 press release.

“It makes video completely searchable. The software creates an audio transcript and record of faces and text in each video through an automated system, which means an officer or investigator can type in a person's name or keywords like drugs and search for when and where it was spoken in the video.”

The police also use advanced software, like the one from Palantir, to automatically analyze the massive troves of data at their disposal, including arrest records, jail phone call logs, parole and probation records, incident reports and interview cards. The NOPD’s field interview cards in particular raised privacy concerns soon after they were introduced in 2011, when The Times-Picayune reported that the police had used the cards to collect and store names and personal information of 70,000 people in just a year.

Brian Hofer, chair of the Oakland Privacy Advisory Commission, told The Lens that while many of the records held by the city and police may not seem very intrusive in a vacuum, they become exponentially more revealing as they’re connected.

“The individual privacy impact from a single data point, probably low, maybe even zero,” Hofer said.

But when you start connecting the dots, he said, even a relatively small amount of data can paint an intimate portrait of someone’s life. He referenced a 2013 peer-reviewed study in Scientific Reports that found that 95 percent of people could be identified with just four location data points.

“These data points are that revealing,” Hofer said. “We’re creatures of habit. We drive to work the same way, we drive to school the same way.”

Tracy Rosenberg, an activist with the anti-surveillance group Oakland Privacy, said that many surveillance products being marketed to cities — like Palantir’s Gotham software — focus on finding connections, trends and social networks in their own data that would otherwise be nearly invisible to a human investigator.

“The pitch of the surveillance vendors has been we're going to let you get more information, but more importantly we're going to let you integrate it, we're going to take it out of silos, we're going to make the information work together, we're going to put it in one place,” she said. “That is definitely surveillance nirvana.”

She said a major concern for her is how these surveillance products will allow law enforcement to take advantage of government databases that haven’t traditionally been a routine part of police investigations, especially as “smart cities” technologies ramp up municipal data collection.

“If you think about the volume of information that cities collect, which can include public health data, tickets and citations, educational records, voting records, the potential for what we call ‘data fusion’ is kind of extensive,” Rosenberg said.

‘The Wild West’

Oakland, California was one of the first cities in the U.S. to start regulating surveillance at the local level. Hofer said the city’s fight for reform began with a 2013 proposal for a federally funded surveillance network.

“The City of Oakland launched this proposal for a citywide mass surveillance program that would blanket the entire city,” Hofer said. “It was similar to what happened a couple years after that in New Orleans with the Real Time Crime Center.”

City officials hadn’t sought public input on the plan, according to Rosenberg. She said the public ended up finding out “through nothing more than an accident.”

“It really only came out because an employee with the City of Oakland found some paperwork and sent something out to activists saying you might be interested in this,” she said. “We had no guardrails in place, no policies. It was the Wild West.”

Basically, they were where New Orleans is today.

“You didn’t even know the technology was being used,” Hofer said. “What we were doing in Oakland is probably what you guys are doing, submitting a lot of public records requests and poring through agendas and contracts, matching up model numbers and serial numbers and trying to see what was being used. And that takes a lot of effort.”

Rosenberg said there are practical limits to what the public can access through what she referred to as “public records odysseys.”

“For everything we asked, we probably got answers on 20 to 30 percent of it. We still have public records requests that go back to 2014 and 2015 that haven't been answered.”

Oakland activists were able to get the city to back down from the 2013 plan. But that wasn’t the end of the anti-surveillance movement.

“We started thinking about, ‘OK, how do we keep this from happening again?’ ” Rosenberg said. “What is the proactive thing we can do so we don’t have to fight these things after they're sort of 75 percent or more there? … It became a challenge to mobilize citywide and start saying no, you can't move this forward essentially on the basis of inertia and entropy.”

In 2016, the ACLU launched its Community Control Over Police Surveillance, or CCOPS, campaign and created a template ordinance with three central requirements: City Council approval of existing and future surveillance technology, annual public reporting on how those technologies are used and a community advisory committee to make recommendations on surveillance policy.

“The biggest win of the framework, I think, is that it brings everything out into the open,” Hofer said.

Oakland passed its version of a CCOPS law in 2018, among the first cities in the country to do so. According to the ACLU, at least 21 cities, representing a combined 17 million residents, have passed some sort of CCOPS law since 2016 including Nashville, Tennessee; Madison, Wisconsin; New York City and Pittsburgh.

But that still leaves the vast majority of American cities — including New Orleans — without this type of regulation.

“Regulatory efforts are starting to catch up, but we were caught flat-footed,” Rosenberg said. “We're all making it up as we go along. The anti-surveillance movement as it is is maybe a decade old at best. So these are very new challenges we're facing.”

‘I have nothing to hide’

Hofer has worked with organizations across the country, including Eye on Surveillance, and said that every community is different in terms of the level of government monitoring it's willing to accept.

“I'm not an abolitionist. I do think some technology can be used appropriately,” he said. “You can determine yourself in each community where to draw the line. It's up to the residents in that city to determine what they think is appropriate and not appropriate.”

For some outspoken anti-surveillance advocates, the technology that cities like New Orleans are adopting act as an extension of what they see as deeply flawed, biased and overly punitive criminal justice and immigration systems.

“It's a way of controlling the masses, including immigrants,” Santos Alva, an organizer with the local immigrant advocacy organization Congress of Day Laborers, told The Lens through an interpreter. “They don’t mess with people who have a good economic standing in this society. They mess with Black people, they mess with brown people, they mess with immigrants.”

Of course, not everyone feels that way about the police.

“There are certainly people that bring up the argument ‘I have nothing to hide,’ ” New York-based privacy advocate Albert Fox Cahn told The Lens.

“Especially with police being as polarizing a topic as they are right now, there are many people who will reflexively talk about their desire to stand in solidarity with the police, a sort of ideological alignment. But even those individuals, when you talk about some of these cases that get to points of sensitivity in their own lives, it's a very different reaction.”

Polling from the Pew Research Center shows that when it comes to government surveillance, the majority of Americans are concerned, believe the risks outweigh the benefits and have little to no idea about what’s being done with the information collected from them or what privacy laws are on the books.

“We all have facets of our lives that make us feel vulnerable when they're tracked or exposed. And it’s different for different stakeholders,” Cahn said.

Some people, he said, might feel the greatest concern about police targeting people based on their religious affiliations. Others may be more skeptical of the government spying on political organizations or creating a database of gun owners.

The Pew poll indicated that for many Americans, there is greater concern around data collected by private companies than government surveillance.

But, Hofer said, “Those lines are becoming fuzzy.”

The government is a consumer in the booming market for personal data collected by private companies. Several federal agencies have purchased private smart phone location data. The Treasury Department has purchased employment data from a subsidiary of the credit bureau Equifax to help determine eligibility for food stamps and disability benefits.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has a contract with a Swedish company that collects data from cars — including navigation history and information from bluetooth connected devices. The popular home security Ring “video doorbells” share footage with thousands of police departments. In New Orleans, a program called Leads Online provides access to hundreds of millions of pawn shop purchase records.

Maass argued that the upsurge of mass government data collection isn’t only a privacy issue, it’s a security issue as well, especially when it comes to small, local agencies.

“Police departments don’t have tech-company-class cyber security professionals who are just locking down their system and doing security audits,” he said.

In 2015, Maass co-wrote a report about how three police departments just outside of New Orleans — St. Tammany Parish Sheriff’s Office, Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Office, and the Kenner Police — left their license plate reader systems completely exposed.

“There were license plate readers where you could just go to a URL, on a website, and bring up the camera,” Maass said. “You could bring up the control, you could siphon off the data as it was coming in, you could watch the live footage. And nobody had actually done the actual investment to protect the software, no one had done the due diligence.”

Williams said he had similar concerns about the city entering surveillance contracts with private vendors, comparing the city to a product consumer who blindly agrees to a long terms and conditions document.

“The same way you can click a box without reading a 40-page document, that same thing is happening with municipalities across the country as it relates to technology,” he said.

Some advocates also have doubts about the city’s role as a steward of all this data. In December 2019, New Orleans was hit by a cyber attack that locked the city out of its own data and systems. It took millions of dollars and a full year to recover.

The city has said it upgraded its cybersecurity procedures during the recovery process. But even then, it’s difficult to know if the city will ever be fully protected when some of the country’s most sensitive and secretive government agencies have been compromised by cyber attacks in recent years.

‘Who was lying?'

Eye on Surveillance and other local advocates have proven it’s possible to push back on the city’s surveillance expansion. But their successes in halting surveillance initiatives come with an important caveat: the public needs to know they exist first.

Public pressure forced the City Council to drop a controversial ordinance in 2018 that would have forced every alcohol vendor in the city to install surveillance cameras directly connected to the Real Time Crime Center. The same year, when the NOPD’s use of the Palantir software caused a public backlash, the city announced it wouldn’t renew the contract. And soon after the NOPD admitted it was using facial recognition in 2020, the City Council banned the use of facial recognition.

But the public rarely gets any advanced warning of new surveillance initiatives. Expansions are often simply announced, rather than brought up for public debate. Other times the public is never informed at all.

“We can't regulate or prohibit technologies that we don’t know exist, that we don’t know our police department might be using,” Hofer said.

Part of the problem, advocates argue, is an intentional tactic from city officials to avoid public debate and controversy. But they said the issue goes beyond just secrecy from individual officials, and that there are institutional obstacles to transparency that arise from the city's near total lack of internal oversight.

Those obstacles can persist even when government officials attempt to be transparent. For example, during the two years the NOPD was using facial recognition, city leaders and elected officials repeatedly and falsely claimed the opposite. But not all of those officials knew they were lying.

“It's unclear to me personally who was lying and who didn't know what they should have known,” Hamilton said.

City Council members, for their part, had every reason to believe the technology wasn’t being used. At a July 2020 hearing, council members asked the city’s Chief Technology Officer and the administrator of the Real Time Crime Center whether the city was using facial recognition. And repeatedly, those officials assured them it was not.

“Of course the city doesn’t deploy any facial recognition technology in a law enforcement purpose,” RTCC administrator Ross Bourgeois told the council. “The city doesn’t have any of that technology available for our use.”

Just a few months later, when it was revealed that wasn't true, NOPD Superintendent Shaun Ferguson told the City Council that he was just as surprised as they were.

“I had no idea we even had access to this. So it's nothing we ever tried to hide at any point in time,” Ferguson said. “I have since learned that our department did not have a policy with regards to using this tool.”

That doesn’t bring much comfort to Marvin Arnold, an organizer with Eye on Surveillance.

“I don’t know which is better, if they lied about facial recognition or if the chief just didn't know,” Arnold said. “I've seen how little the public and even the city itself knows about these systems. I don’t think the majority of council members understand what city surveillance looks like. I don’t even think our city administrators understand it. So how can your average resident?”

Maass leads the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Atlas of Surveillance, an attempt to identify and map local and state surveillance usage. He said one of the major obstacles was dealing with officials who were unaware of the surveillance technology being used within their own government.

“That is a huge problem,” Maass said. “I'll file a public records request and the agency will come back and say, 'Well we don't use that technology.' And I actually have to show them the receipts, like, yes you do. Then they check back again and they're like, 'Oh yeah, I guess we didn’t know.’ This happens all the time, all over the country.”

Similarly, when the city’s use of the Palantir software was revealed six years after it began, there was a debate over how intentionally secretive the city had been.

When The Verge broke the news, the headline read, “Palantir has secretly been using New Orleans to test its predictive policing technology.”

A few days after that article, The Times-Picayune called the relationship “a not-so-secret secret,” pointing out that the software was disclosed on the city-run website for former-Mayor Landrieu’s NOLA for Life program as well as a public report from 2016.

“The reporting on the use of the Palantir technology was false and misleading,” Ryan Berni, one of Landrieu’s top deputies, said in a recent interview. “It should not have been a secret for anyone who was paying attention to the NOLA for Life program.”

Nonetheless, much of the public was unaware of the city’s relationship with Palantir, as were members of the City Council and the city’s Office of the Independent Police Monitor. And many residents wondered how the city could have avoided any sort of public vetting before entering the Palantir contract.

The answer is that there simply wasn’t any public process or disclosure requirement for the city to evade.

Most city contracts don’t require City Council approval or a public hearing. And the city doesn’t have to issue press releases every time it signs a contract. Many of those records are available to the public upon request. But until someone asks, the city has no legal obligation to announce its use of surveillance technology any more than it has to announce its use of Microsoft Word.

Even if you do get a hold of a city contract, they are often vague. In the Palantir contract, for example, the company’s responsibilities are simply listed as providing the city with “such technological data as necessary to deploy the Project.”

In fact, at the same time as the city was using the Palantir software, it was using another, very similar piece of software called Coplink by Forensic Logic. Coplink and Palantir’s software are often referred to as market rivals. Ronal Serpas, who was the Police Superintendent when the city first adopted Palantir, compared it to Coplink in a 2018 interview with Fox 8.

The Coplink software never received the widespread attention drawn by the Palantir contract, and the city continued using Coplink without controversy up until April 2021, when the contract expired, according to the NOPD.

Berni said the lack of City Council input on surveillance decisions is due to New Orleans’ “strong executive” model of government, in which the mayor decides the vast majority of day-to-day operational decisions.

“We have a system set up where there's a clear mandate where the executive and all the departments and agencies under it run the government,” he said. “The council is there to set the budget and big picture policy. And at various times, decides to get more in the weeds on specific issues. I think that's for the council to decide.”

‘It's not gonna stop’

The city of New Orleans grew its surveillance capabilities with little pushback from members of the City Council until, in early 2020, a seemingly innocuous proposal about streetlights came before the council’s Smart and Sustainable Cities Committee.

The proposal called for a pilot program to introduce 146 “smart street lights” equipped with video and audio recording. The cameras weren’t primarily for police use, city officials said, and would be mainly used to study traffic patterns. But the footage would be made available to the Real Time Crime Center.

At the same time, the city of San Diego was facing a public backlash over the same street lights. The city had installed over 3,000 of them in 2017. But many residents were disturbed after finding out in 2019 that the police had started using the camera footage for their investigations. The reaction was so strong that San Diego’s City Council is now poised to pass a comprehensive CCOPS ordinance, and has turned off the smart street light cameras until it does.

The smart street lights hit a nerve in New Orleans as well. Members of Eye on Surveillance were frustrated that they were once again caught off-guard by a surveillance proposal.

“I guarantee that instead of saying they were having a meeting about smart cities, they said they were having a meeting about adding 146 more cameras, a lot more people would attend,” Arnold told The Lens at the time. “Overall, the onus has been on the community to find out the specifics rather than them being forthcoming.”

In a somewhat surprising turn, then-Councilman Williams decided to put the smart cities pilot on hold until the council could pass comprehensive surveillance regulation similar to CCOPS legislation in other cities. He said that the decision was heavily influenced by the work of Eye on Surveillance advocates.

But not everyone on the City Council had the same appetite for regulation. Some didn’t want to take a “tool out of the toolbox” for police, or insisted that their constituents wanted more surveillance, not less. Others worried about the administrative burden of tracking all that technology.

The City Council ended up cutting almost all the forward-looking provisions from the ordinance, the ones meant to create an ongoing regulatory structure for surveillance. The only explanation given during the meeting was simply that the NOPD had asked them to remove those pieces of the law.

“We've stripped extensive approval and reporting processes as requested by the NOPD,” Williams said during a December council meeting.

The NOPD didn’t respond to questions about its alleged request to change the legislation.

What the council passed instead was a full ban on four types of technology: facial recognition, predictive policing, characteristic tracking software and cell-site simulators, also known as stingrays.

The ordinance was no small achievement. New Orleans is just one of a handful of cities in the country to outlaw facial recognition and predictive policing. It’s likely the first city to outlaw stingrays. And the law sets up a framework to create future guardrails.

But activists, both in New Orleans and nationally, say that individual bans, without any high level oversight or regulation, just aren't enough to keep the surveillance state in check.

“The problem there is you've intervened effectively on four kinds of surveillance technology, and everything else is left untouched,” Rosenberg said. “And for the moment, that probably has some efficacy. But as time moves on and technology marches on, there will be new things down the road that potentially are just as disturbing as those you chose to ban."

Advocates also point out that without those oversight measures, there’s no sure way to verify whether those bans are even being followed, considering that the city falsely claimed it wasn't using facial recognition for years.

And already, the NOPD is working to walk back at least the facial recognition ban. Councilman Jay Banks told The Lens that the NOPD was working on a policy on how it would use facial recognition and that he would support reversing the ban if the policy was sound.

Meanwhile, although the City Council abandoned the smart cities pilot program, the city is moving ahead with an even bigger version of the project. It recently selected a contractor to implement a broad smart cities program that would, according to the contractor’s proposal, include 3,000 smart street lights, each of which would have at least two cameras.

“It's not a one and done,” Hofer said. “It's not gonna stop and it's not gonna slow down.”

- Project concept and production by Caroline Sinders and Michael Isaac Stein

- Writing, research and reporting by Michael Isaac Stein

- Creative direction, research and design by Caroline Sinders

- Data visualization, research and graphic design by Winnie Yoe

- Web development and technical guidance by Annabel Church and Thomas Thoren

- Editorial support by The Lens

- Project funded by the Fund for Investigative Journalism